Reports Previous Workshops

Sixth Workshop – 27 to 29 September 2016 – Warth (Switzerland)

Module 4 – VoD platforms as commissioners and distributors of original content. For good or for bad?

Introduction

VoD platforms have started to commission content (TV series and feature films) they tend to distribute exclusively on their networks. They position themselves also as distributors by buying worldwide rights and ask to “premiere” the film before theatrical release.

Or, in other words:

- Those strategies raise many questions: what will be the impact of those new players on content?

- How will new business models challenge public funds not only in terms of financing but also on distribution strategy?

Case Study / SKW Schwartz – VoD platforms as commissioners and distributors of original content

Please also see Florian Hensel’s presentation (PDF)

Trends in content

- The content is increasingly coming through VoD services because the VoD audience is growing

- VoD platforms can produce the original content totally outside of the traditional exploitation landscape.

- There are two types of VoD content:

- Traditional art-house European films financed though public film funds

- New highly developed series produced either by the providers of VoD services or by the US companies like HBO

- There have been changes in terms of quantity. Over the past four years the original content shown on Netflix has increased by 3050%

- In 2012, only a quarter of the produced shows ended up on Netflix. Today, Netflix offers more content than any other existing network or cable channel

- A slight increase exists also when it comes to traditional art-house films – from two original productions in 2012 to seventeen in 2016

- Unscripted series have the biggest increase (from 1 to 35).

- The practice of a simultaneous theatrical, DVD and VoD release has been increasingly popular.

But

- The European VoD market is much less developed than the one in the US

- In Europe, there are seventy-five VoD services, plus a handful of subscription VoD services. Out of these seventy-five, only one or two have a footprint on more than two countries.

- There is still no functional VoD platform at the European level

- In some parts of Europe (for example, Nordic region), there is much more competition due to multiple small platforms, but the VOD landscape is changing. The competition will be reduced to Netflix, HBO, Amazon Prime and the biggest national VoD services

- Public broadcasters perceive VoD platforms as fierce competitors because they risk losing all VoD rights.

- The role of public film funds in Europe is mostly passive when it comes to VoD

- There are still no concrete Europe-related data on:

- How are consumption habits changing?

- Who are the people who consume VoD services? and

- Is everything that should be on VoD already on VoD?

Case Study: Independent research by Prof. Hennig-Thurau from the University of Münster based on individual data-gathering

Prof. Hennig-Thurau interviewed around 4000 people about the new series distributed via VoD platforms. His objective was to discover what makes these series more popular than traditional old series. He reached the following conclusions:

- The new series have much better quality. They are constantly getting better and better

- The new series are not extreme and niche as one would think

- There may be slight differences in the demographics. Older people want to watch HOMELAND for example, but young ones would go for TRUE DETECTIVE

- The new series are increasingly consumed via VoD, not via free TV.

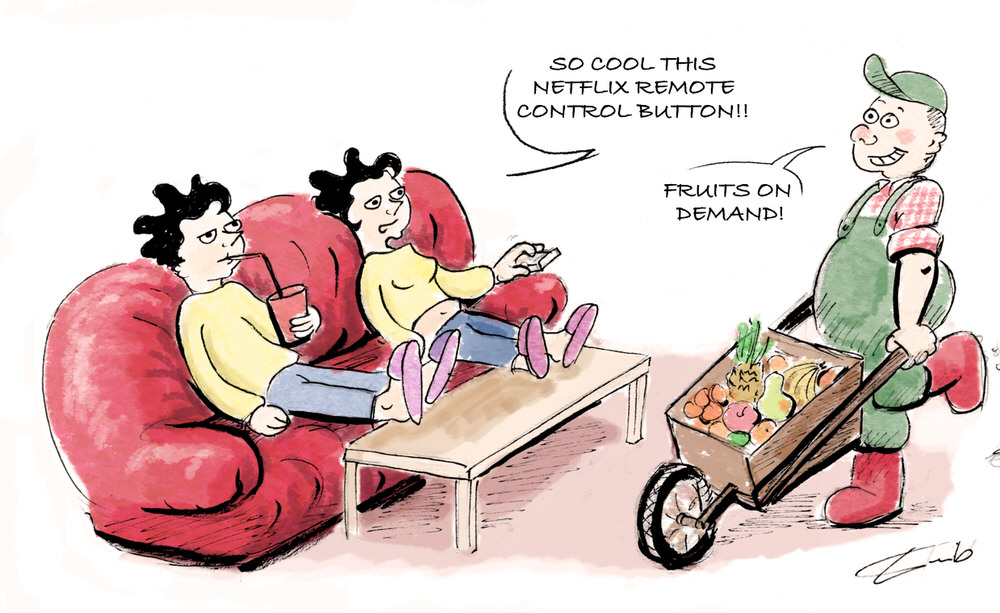

- Today, people often buy TV sets only because it has a Netflix button on the remote-controller. They seek for an easier access to VoD via their TV sets.

What can film funds learn from Netflix and Amazon?

The traditional funding system still does not see enough potential in VoD:

- The European Audiovisual Observatory’s data indicate that from 2005 to 2014 almost 17000 films were theatrically released in the EU (2800 from the US and around 11000 from the EU). While almost all of the American films (87%) were additionally released on the VoD services, only 5000 EU films (47%) had VoD release. Thus, Around 5000 EU films disappeared after the theatrical release.

- In Europe, the VoD release is too complicated. Where is the flaw in the system?

The success of Netflix and Amazon is based on:

- Having reliable data

- Spending a lot of money on experiments until they create profitable content. For example, Netflix is currently doing local services in Poland and Turkey, trying to move from playing global content to localizing the service and creating local content.

VoD release in Germany

Challenges of VoD licensing

- Legal framework regarding the ownership and use of VoD rights in Germany (Civil Code, Copyright Act, etc.).

- A variety of unsynchronized film funds and policies: public funds (national and regional), Film Funding Act, funding regulations and guidelines.

- Public and private broadcasters traditionally invest as co-producers in films and they have their own terms of trade defining what kind of exploitation is allowed. The same applies to TV productions.

- The Interstate Broadcasting Treaty imposes certain programming and production requirements. Broadcasters have to ensure that the audience gets a wide variety of opinions, which can limit the exploitation.

Programming conflict

Multiple partners (broadcasters, sales agents, distributors, VoD platforms) often meet together in the financing. Balancing them is extremely complicated and influences the exploitation cycle of a specific project:

- VoD plays role for pay TV because VoD is a way to extend the exploitation of a specific content before it ends up on free TV.

- From the broadcaster’s point of view, VoD is just an extended broadcasting window. There must be no VoD exploitation (both transactional and SVoD) during free TV cycle, which can last up to 36 months.

- World sales agents do not want to have restrictions at all.

VoD Licensing for commissioned TV productions

- The broadcasters can commission productions from production companies. They can take away the VoD rights from producers, but keep producers entitled to a share of VoD revenues. If TV does not manage to exploit VoD rights, then producers shall receive the rights back and try to sell the content themselves

- Alternatively, the broadcaster can simply put money on the table and buy all the rights. It should be a considerable amount of money equal to the aggregate sum of the world sales revenues. Such deals can allow the theatrical window for 30 to 60 days after which they get the SVoD rights in as many languages as possible and as many territories as possible.

VoD Licensing for commissioned VoD productions

- Broadcasters demand that free TV period lasts three years during which there could be no VoD exploitation. Is there a way to exclude the broadcaster out of financing and try something completely different if another partner offers enough money as compensation?

- The Sales agent can say to a producer – “try to get me as many SVoD rights as possible, and I will pay you for each territory”. Therefore, these VoD rights, instead of staying with the local distributor, should be given to the sale agents who will try to sell the whole package – as much as possible.

- There is a distribution fight going on. Exhibitors want to keep their share of cake, but if new players with a substantial amount of money on the table appear, then the situation can change. The new player can be Netflix or another VoD player. However, this principle usually works only with the new TV series, whereas the feature films follow totally separate patterns. There is an example of Netflix co-producing with the BBC and German public broadcaster ZDF for children’s TV series. The ZDF did German distribution, BBC did UK distribution, whereas the rest of the world was under NETFLIX in all forms.

Windowing in Germany (see graph in Florian Hensel’s presentation – PDF)

- The purpose of windowing in Germany is to maximize revenues for “high value rights”

- The method they chose to achieve this is creation of (exclusive) windows and/or contractual holdbacks and/or black periods. The examples of windowing in Germany:

- Holdback of any Free VoD for the benefit of Pay VoD (in Germany statutory holdbacks apply)

- Holdback of SVoD for the benefit of TVoD

- Holdback of DVoD for the benefit of Pay TV

- 1 month black period of VoD before Free TV release

- 12 (or even 36) months black period for VoD during Free TV

- Worldwide holdback of any VoD prior to the respective US relese

But

- Coordination of releases, holdbacks, black periods and exclusivity becomes more and more complex

- If you sell the content directly to the VoD platform, you can sell it at the price of free TV, without bothering with blackouts and windowing

Outcomes of group discussions

- The Swiss Federal Fund for Culture supports straight-to-VOD productions and will introduce a selective scheme in 2017 to finance digital promotion of contents aimed at Swiss consumers. According to the new legislation, producers are obliged to submit reports on all VOD activities and releases in order to help the fund collect statistics necessary for formulating funding guidelines within the VoD scheme. Within this scheme VoD platfroms (such as Netflix) can be a co-producer

- Norwegian Film Institute is also opening a new scheme for VoD platform, but is unsure about a possible impact of such a scheme since there is no data to measure it which is not the case for the theatrical market. There are statistics all over Europe that help in monitoring and evaluation of every step within theatrical schemes

- In Germany, the budget of the German Federal Film Board (FFA) is financed via the so-called film levy which is raised from, among others, the cinemas, the video industry and television. They are forced to share data on their revenues because it is necessary for calculation of their levy. VoD service-providers should be levied, because it would force them to disclose data about their revenues for the purpose of the levy calculation. This levy has already been introduced in Germany, and the idea is that the German example should be followed by all other European countries and also regulated at the EU level through the European Commission. This strategy would ideally lead to getting more data on VoD services.

- Danish Film Institute is also in the process of opening the funding system to the VoD platforms. However, the regulations demand that every applicant must provide consumption data. For this reason, Netflix will probably not apply in the years to come. The VoD schemes will probably be more attractive for small platforms. There is already a TV funding scheme where even Netflix can apply as long as their services and products target Danish audiences. They have never applied directly, though. They only co-financed a TV series produced by the Danish Public broadcaster.

- MEDIA Programme has a scheme where five European countries need to distribute one European series through national VoD platforms. The Audiovisual Media Service Directive (AVMSD) is being under revision and there is a proposal that broadcasters should include VoD content.

Collaboration opportunities between traditional and new players

- In Austria, there is one start-up company dealing with VoD. It used to be co-financed by MEDIA Porgramme, but the Austrian broadcaster has recently become the majority partner, which led to a diversification of broadcaster’s activity and synergy between TV and VoD.

- Despite a huge penetration of Netflix (in some countries up to 40%), there are still national and regional platforms that are doing well. Broadcasters set-up VoD platforms and create content with the unique selling point, like Danish TV drama. This can lead to co-production deals with Netflix as well.

- Netflix sometimes takes models from the traditional TV. They sometimes decide, just as TV, not to put all episodes at once, but make the audience wait for a week for another episode, like the series DESIGNATED SURVIVOR.

- The Film funds should be teaming up more with local VoD platforms that encourage cultural value and diversity. Netflix or HBO are business-driven content providers. They want to reach the entire national market with every product. Do public funds have a responsibility to invest into national film platform to help the cultural films they support get seen by a broader audience?

- Netflix sometimes buys small, art-house films (it happened once in Flanders). However, it stays unclear if Netflix did it because they are really interested in buying such films or it was just a one-off action for the purpose of testing. Due to the lack of data, it is not possible to know if this will happen again in the future, but it still sets the ground for a potential collaboration.

- VoD platforms would commission more feature films if the funds made sure that projects could be produced faster. Currently it takes three to five years to produce a film (especially a co-production), which is too long for VoD platforms

- Netflix or another VoD platform can sometimes replace distributor and pre-buy a film on the basis of a script. They already produce their own local content in France and Germany.

The Development of Content: Challenges and Opportunities – Public Funds as Pawns or Players?

- Introduction – Scriptwriting and development funding landscape

- Module 1 – Evaluation of funds' portfolio

- Module 2 – Scriptwriting and Development Support: funding landscape, co-development initiatives and development strategies, successful or unsuccessful stories

- Module 3 – Automatic schemes: more about sustaining production companies than developing quality projects?

- Module 4 – VoD platforms as commissioners and distributors of original content. For good or for bad?

- Module 5 – Talent support initiatives

- Module 6 – Hybrid contents: the mix of different artistic disciplines

- Module 7 – Development – An underestimated stage in the production process?

Illustrations by Séverine Leibundgut

Schedules Previous Workshops Partners Contact