Reports Previous Workshops

Fifth Workshop – Tuesday 29 September to Thursday 1 October 2015 in Santpoort, Netherlands

Module 2 – Co-productions: Financing issues: for the producers, for the funds

(specific programmes, decision timeline, recoupment, financial co-production)

Introduction

Majority co-productions are considered as national productions and are financed at the same level. The financing of minority ones is a real challenge for the funds.

In other words:

- Is it the solution to create, like some funds do, specific programmes dedicated to minority co-productions?

- Do programmes really help producers to develop reciprocity partnerships?

- Can treaties combine both cultural/qualitative and economic aspects?

- Can we imagine a future where the concept of cooperation goes beyond the device of official co-productions (i.e national treatment) with its thresholds and percentages?

- How to revise the system on the national level so that it enables better collaborations on the international level?

Reflections on minority co-productions (and other stories)

Roberto Olla, CEO of Eurimages

Please also see Roberto Olla’s presentation (PDF)

Note: Some text below and financing plans are derived from Roberto Olla’s presentation (in italic). They are copied in this report for a better understanding of the discussion that took place within the group.

Are minority co-productions all-good?

“Tradition wants it that minority co-productions are beneficial for the national/local industry because they…

- stimulate the internationalisation of the national film industry (exchange of film professionals/good practices)

- bring inward investments (e.g. fiscal incentives)

- open new markets (especially if there is an artistic cooperation: actors/locations/story etc.)

- de-provincialize national cinema (content-wise)"

Minority co-production financing schemes

- Selective funding (based on statistics)

- Only the countries with separate minority co-production schemes do minority co-productions (examples of Belgium and Croatia).

- In other countries, like Italy and Romania, minority co-productions compete with national films and national/majority co-productions within the same fund.

- Some countries, like Turkey, simply ignore minority co-productions.

- Fiscal incentives (tax shelter, tax credit, rebates, spend-based financing)

- The majority of European countries with fiscal incentives are open for minority co-productions in order to attract investments.

- However, some countries like the UK and France tend to narrow down such fiscal incentives only to majority co-productions and national films, using very selective cultural tests

- Industry-based funding:

- Minima guarantees or TV presales are possible but only from big market countries.

- Minority co-productions can also be financed through in-kind investment or own investment.

Share of Revenues

Depending on the type of financing raised, revenues can be shared:

- Proportionally: according to co-production treaties, producers share rights and revenues proportionately to their financial investment.

- Non-proportionately if a minority co-producer acts only as a production manager or line producer whose financing is purely automatic or simply spend-driven.

But

- In reality, when it comes to sharing revenues, pre-sales and other resources from the third countries, producers tend to share them proportionately only if they are all involved in the making of a film and all bear a certain degree of financial risk.

Case Studies: Minority Co-productions

(Titles and names of directors and producers are intentionally left out)

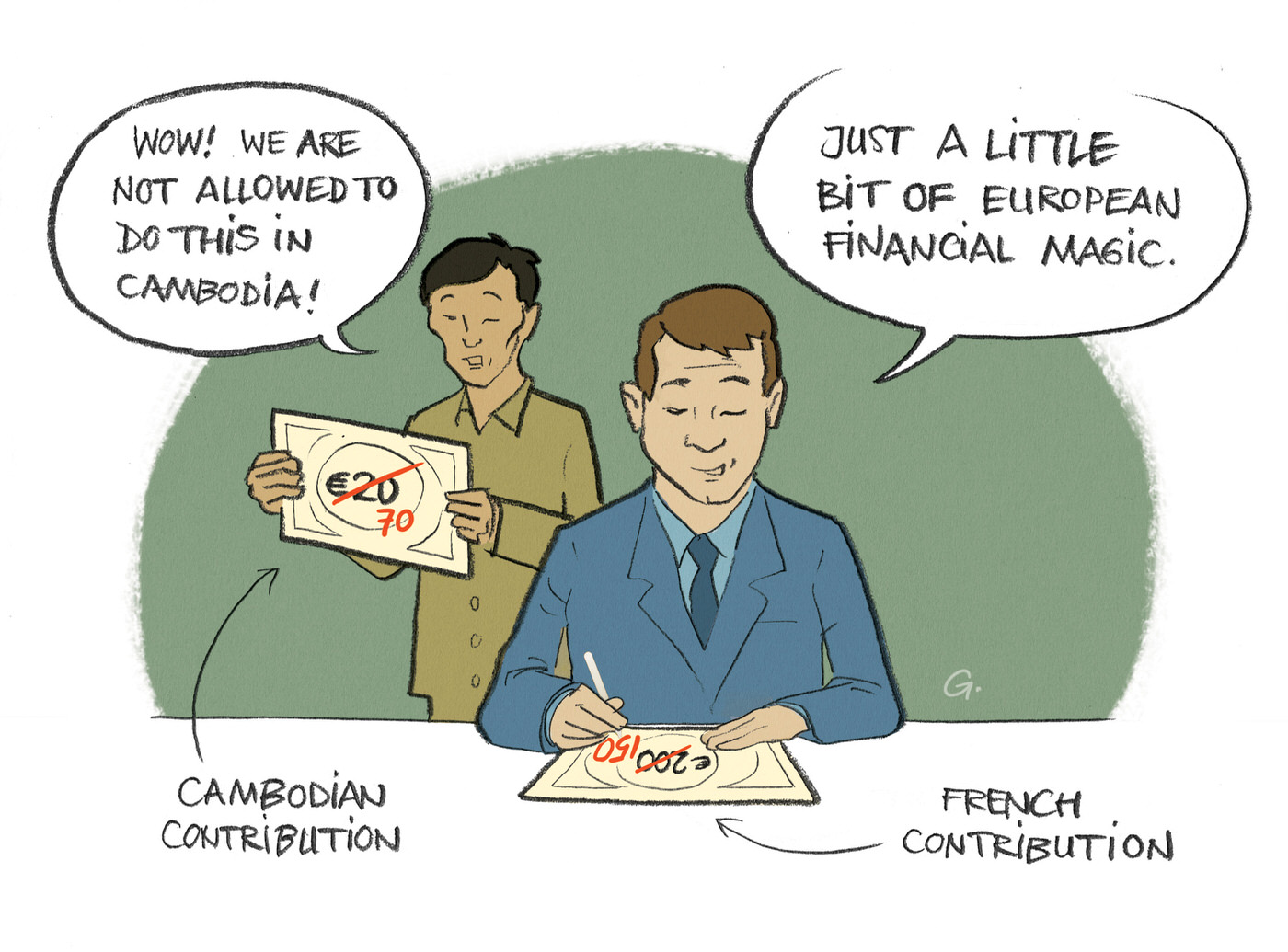

CASE 1 – France 70%/Belgium 20%/Cambodia 10%

Co-production set-up

Financing Process:

| France (70%) | The French part of financing includes selective support from France, MEDIA grant, French share of the Eurimages support, a share of the world sales, financing from public French TV (obliged by law to finance feature films). |

|---|---|

| Belgium (20%) |

|

| Cambodia (10%) |

|

Share of revenues

According to the co-production treaty:

- World rights are supposed to be shared 70% – 20% – 10%.

- Each co-producer would keep their domestic territory (France would keep France, Belgium would keep Benelux, and Cambodia would keep Cambodia or some other connected territories).

- The “rest of the world” (ROW) would be shared proportionately to the financing.

But

- This type of co-production treaty that received official certifications from competent authorities and Eurimages support is basically a national film. In this case a French film.

- The Belgian producer did nothing but the application for the Belgian tax-shelter. He/she was not involved in the development of the project, finding the cast and other creative elements.

- The co-producers calculated how much of the risk money each of them raised (which in case of the Belgian co-producer was only private investment). It was agreed that after the minority co-producers recouped the risk money, they can get only 2.5% of the further revenues coming from ROW, which is far from proportional to the official financial share.

- It is paradoxical that this film is counted as a Belgian official co-production and consequently increased the contribution that the Belgian government needs to pay to Eurimages based on the quantity and volume of co-produced projects.

Conclusions:

- The only benefit of this particular minority co-production was attracting inward investment. It did not, facilitate opening up to other markets and international collaboration between the teams. Nobody will see a single Belgian element in this film.

- Too few benefits to minority co-producers

- When there is no true artistic and technical collaboration, when co-production is not organic from the beginning and when producers do not develop the projects together, all reasons why one may want to do minority co-production fall through.

- Importance for co-producers to work together early on by co-developing their projects

- Tax shelters tend to enable co-productions without risk-taking and true collaboration, even if certified as treaty co-productions due to the local spend and technical collaboration.

- Tax and automatic schemes need to be reformed

- Sometimes political objectives overcome cultural and industrial ones.

CASE 2 – Denmark 70% / Norway 20% / Czech Republic 10%

Co-production set-up

Financing process:

| Denmark (70%) |

|

|---|---|

| Norway (20%) |

|

| Czech Republic (10%) |

|

Share of Revenues

According to the European Convention on Cinematographic Co-production that was applied to this co-production, the world sales and revenues (except for the domestic territories) are supposed to be shared “pro rata”.

But

- In reality, the Danish producer negotiated basically everything, even with the Swedish and Norwegian financiers. His/her workload and the risk he/she took were much higher than the percentage of financing he/she officially secured.

- Therefore, the producers isolated the percentages of their own investment (“risk money”) and calculated the percentage for sharing revenues accordingly:

- Revenues from the five Nordic countries were shared only between the Scandinavian co-producers.

- The Czech producer was given the revenues coming from Czech Republic and double the amount of his/her participation when it came to the ROW. However, he/she earned nothing because the film was intended only for the Nordic region.

Conclusions

- Sharing of the revenues is not done pro-rata as is envisaged by co-production, but according to who does what in a co-production.

- The minority co-producer is often only a line-producer. He/she is not engaged in the script, and casting and bears no risk in securing the financing.

- A minority co-production is often not more than a service deal, but producers tend to present the project as a co-production because it looks much more convincing in a Eurimages applications (especially if an exotic country is involved).

The Myth of Reciprocity (alias Quantity vs. Quality)

- In the absence of natural co-productions reciprocity is a way to balance unbalanced relations (for example, lack of interest in your national cinematography from a co-producing country). The reciprocity is about “do we favour quality or quantity?” and it works if the interest in co-producing between two countries is one-way only.

- Exchange approach: Reciprocity between small countries is a way to guarantee support for their own projects that otherwise would not come into life given the size of the budget and the dimension of the countries. It is the case in the Baltic countries that would have a hard time if they do not co-produce among each other. It is easier for them to leave a little money aside for minority co-productions, so that their expensive films can in return get funding from other countries.

- Reciprocity for political reasons: It is practiced for the purpose of establishing good relations for reasons beyond cinema. Such reciprocity arrangements are usually made with big and rich countries like France or Germany.

But

- Reciprocity has little to do with quality.

- It undermines the major mission of public film funds to support films that are original, innovative and possible only with their support.

How to avoid reciprocity measures?

- Viable and credible alternative to reciprocity could be co-development schemes. The funds should enable producers to work together from the beginning, not only when a project is developed and budget closed. Co-development funds would be particularly useful for smaller countries. For bigger countries co-producing is just a way to close the gap in financing.

- Organising training where you would teach producers how to co-produce and collaborate beyond their national territories. It is crucial for co-producers to share the same vision for the film, and not just look for a country where there is money.

…beyond the Treaties

- Is co-production necessarily linked to the practice of treaties?

- Can we imagine a future where the concept of cooperation goes beyond the device of official co-productions (i.e. national treatment) with its thresholds and percentages?

- If cinema co-production could be understood differently, the parameter of “minority co-production” will become obsolete and cooperation will be measured otherwise.

In other words:

- Once producers learn how to collaborate, they do not need treaties anymore. The only requirements should be to find quality projects, local co-producer(s) and investment(s) coming from all co-producing countries.

- Many countries in Europe are so much used to producing with one another that the rigidity of the treaties only affects the quality of both the films and the communication of the producers involved.

- Treaties should not cover co-productions where financing comes only from economy-oriented sources (automatic tax-shelters or regional funds).

- Countries should keep treaties only with those countries that have not yet experienced co-production, but once producers can work without them, treaties should be removed. You can access the Irish Film Board funds, for example, without a treaty. However, it would be impossible with countries like France and Belgium.

Outcome of group discussion

What role do minority co-productions play in European countries?

Luxembourg Film Fund

They work differently depending on the size of the country and common language. As they didn’t have a potent cinematography before, their industry evolves and has been trained through minority co-productions.

Uruguayan Film Fund

In Uruguay, the industry is based on majority co-productions. Minority co-productions are possible only through reciprocity measures.

The Netherlands Film Fund

Co-production treaties need to include co-development as well, for the sake of establishing long-term relationships between the funds and industries.

Wallonia Brussels Federation

Treaties (except with Luxembourg), protect their projects from being taken over by bigger countries like France.

German Federal Film Board

Minority co-productions in Germany are mostly done through regional funds, and they consider them only as co-financing. However, they also have some co-development agreements (with Italy and very soon with Norway), because they find that it is important to collaborate from the beginning if they intend to make natural co-productions.

Austrian Film Institute

Things work well among comparable countries. For smaller countries with big neighbours that speak the same language it can be complicated. One never knows if it is an advantage or disadvantage. This can also lead to a problem of identifying national cinema. People mistake Austrian films for German films, Belgian films for French films and Canadian for American.

Ontario Media Development Corporation

They recently had a co-production with Ireland. It was an Irish director adapting a Canadian novel. However, despite all these elements audiences perceived this film as a US film because of the language. So the structure of financing is one thing, but the perspective of the audience is completely another thing when it comes to the identity of minority co-productions.

Eurimages

People are confusing financial co-productions – where both producers are making financial contribution through taking risks – with co-productions based only on tax credit(s) where the line producer is an accountant.

Concluding remarks

- Within the existing co-production paradigm in Europe, minority co-producers enjoy fewer benefits than expected.

- Co-development initiatives can lead to more natural co-productions and creative participation of minority co-producers.

- Adequate revision of automatic schemes and tax-shelters can lead to more natural co-productions.

- Political objectives sometimes overrule the cultural and industrial ones.

International co-productions, Development, Gender and quotas

- Module 1 – Co-production Landscape (volume, co-production treaties, cinema vs television, financial, non-official)

- Module 2 – Co-productions: Financing issues: for the producers, for the funds (specific programmes, decision timeline, recoupment, financial co-production)

- Module 3 – Co-productions: Legal and Financial Issues

- Module 4 – Distribution: co-production opens access to other countries, does the audience follow?

- Module 5 – Gender / Quotas Issue – Update on Funds’ Strategies

- Module 6 – What to foresee in the next ten years based on what’s going on now?

- Module 7 – Development – An underestimated stage in the production process?

Illustrations by Gijs van der Lelij

Schedules Previous Workshops Partners Contact