Reports Previous Workshops

Ninth Workshop – 25 to 27 September 2019 in Potsdam, Berlin

Module 4.1: Digitisation From Application to Distribution

Introduction

As presented during the previous MEDICI workshop, the blockchain could be adapted to public film funding. That is possible because the blockchain technology correlates with the process of digitisation which most of the public film funds currently use to digitise their funding documents, and because most of the public film funds produce, co-produce, acquire and distribute content. They have to deal with a wide variety of different types of contracts and stakeholders. That implies a great deal of administrative work and burdens that could be reduced by implementing blockchain architecture. A number of questions arise here:

- What do we need in order to go forward if blockchain were to be THE solution to the burden of administrative work for the funds and the industry?

- Are the needs identical in all funds?

- Is there a possibility to share any of these technological developments rather than create them anew for each funding body and thus lose time and money?

Lecture and Q & A: Florian Glatz

Lawyer and President of the German Federal Blockchain Association

I am here in two capacities:

- As a Founder and the President of the German Federal Blockchain Association, I will talk about the blockchain strategy that the German Government has just published. The blockchain technology is becoming a global phenomenon since the relevant reports have been published in many European countries, United Arab Emirates, China, US, etc. The German strategy is a 30-page document that indicates how Germany should research, support and employ the blockchain technology in many different sectors of both the public administration and the private economy. It contains also a chapter on copyright, referring in particular to the film industry. It says that blockchain might be very relevant for the management and enforcement of copyright.

- I also represent the Motion Protocol project whose mission is to introduce a blockchain-based token infrastructure into the film industry. We perceive blockchain as the digital equivalent to the copyright law. In our view, blockchain is not a product owned by a company or a government, it is simply an idea that is out there and is slowly being implemented in many different sectors. However, blockchain is not the one thing that will save us all. It is just a tool and it is up to every industry to decide how to use it.

Blockchain in a Nutshell

Standardisation, automation and disintermediation are the major trends in today’s society that the blockchain technology is based on.

- The blockchain standardises and represents information and knowledge in a structured and machine-readable form. This standardisation makes machines understand what the humans have done.

- As soon as the machines can understand the information that we are transacting upon, they can start to automate these transactions. The automation happens thanks to software, connected computers and, ultimately, sensors. We can digitally measure everything about this world, which enables a deeper and deeper automation of things.

- Disintermediation means that since computers can automate a lot of processes, many intermediaries that were established in the 20th century will not be needed anymore. Now everything can be done by computer in an automated fashion.

Defining a blockchain

- Blockchain is a megatrend. It is not a particular thing, but a big ideal of many shapes and forms.

- Blockchain does not have the image that represents it. It is an abstract, invisible technology that runs on some computers and you will never see it.

- Blockchain is all about bookkeeping.

- Blockchain is an immutable and append-only database resembling an excel spreadsheet. It is a means to record (store and read) information in a structured fashion. We can store all kinds of information in this database and it will be shared by many people on millions of computers worldwide. Everybody who retains a copy of this database agrees that whatever is being written in this database is true. Therefore, blockchain turns data into facts through the consensus-computing relevant to the people that rely on this database. Blockchain has some very strict and concrete rules about how one can add or modify information in this database, which is what makes it reliable

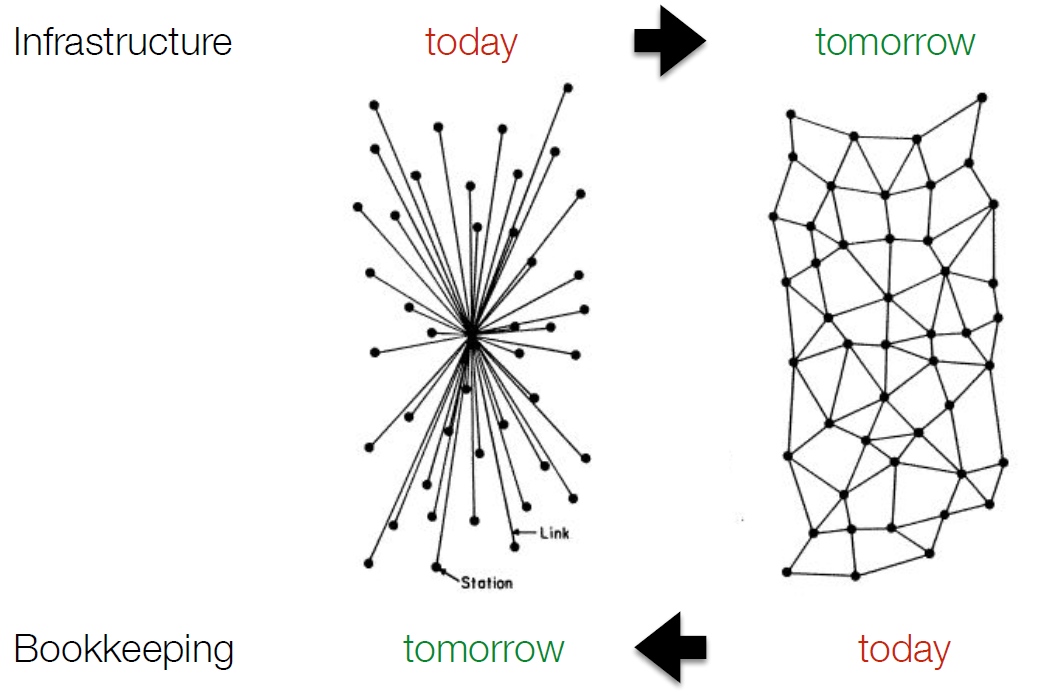

A decentralised infrastructure behind the blockchain

All engines we use today (Google-search, WhatsApp, Facebook, etc.) have a centralised IT infrastructure behind them. Whenever one sends information via e-mail or WhatsApp, it is intermediated through a central server in the centre of this interaction between two peers. This simple architectural solution has a huge impact on the society. Namely, corporations such as Facebook use it to track users, create and sell data about people and earn billions, which has created a whole new concept of privacy.

The blockchain technology, however, ensures a transition from this centralised to a decentralised infrastructure. In the decentralised one, there are no middlemen anymore when information is sent from one peer to another. The blockchain removed the middleman, but retains the notion of a truth that anybody can look into at the same time in order to know what is going on. The first thing that was built with this blockchain-triggered solution was “the money without banks – bitcoin”. But now, ten years later, we are looking at many different applications of this solution to this abstract problem for different industries, including the film industry.

We live in a totally decentralised world. Everybody is doing their own bookkeeping on paper, in an excel sheet, in a word file, in their head…it is a very localised process happening in isolation in millions of different places in our world. The lawyers exist in order to check all those books for mistakes or cheating. But it costs billions or trillions of dollars. The lawyers’ salaries are called transaction costs and the blockchain revolution can finally make them unnecessary. There will be no need for an auditor or lawyer to discover frauds and mistakes because it will happen automatically in the system. To put it shortly, blockchain is centralising booking-keeping on a decentralised bookkeeping infrastructure.

Why Should the Film Industry Care About the Blockchain?

The blockchain technology can be applied to the copyright management in the film industry. The example of the IMDB (International Movie Database) demonstrates this. This database provides countless details of every individual film. But there is only one critical piece of information that is always missing – who owns the film (how many people? Which kinds of royalties do they get when the film is being exploited? In which territory? In which form? etc.). This information does not exist anywhere because it has been created through peer-to-peer distribution licences and contracts. There is no central repository that keeps track of this data. This results in

- a non-transparent market for trading IP rights,

- an information asymmetry at the detriment of filmmakers,

- inefficiencies in the area of clearing film rights and

- impossibility of direct remuneration of rights-owners.

Hence, the main mission for the film industry should be to centralise with blockchain this decentralised way of bookkeeping when it comes to rights management in the film industry. In this regard, it is necessary to create a central registry for film rights and licences, which will ensure

- more transparency for filmmakers, right holders and financers

- a better access to global licence trading

- direct renumeration

- disintermediation of unnecessary middlemen, and

- new business models.

Token Economy as a Solution

The Motion Protocol project I am working for has developed its Intellectual Property (IP) Book-Keeping Protocol that runs on a blockchain. It is based on a very important concept in the blockchain technology called token. Token is an abstract thing – a unique digital identity for an asset.

Could a film be considered as an asset using the concept of token?

A film is an asset created through the existence of the copyright law. This law ensures that a film becomes an economic good with some value. It can be owned, sold, sublicensed, etc.

How do you represent this asset on the blockchain using the concept of token?

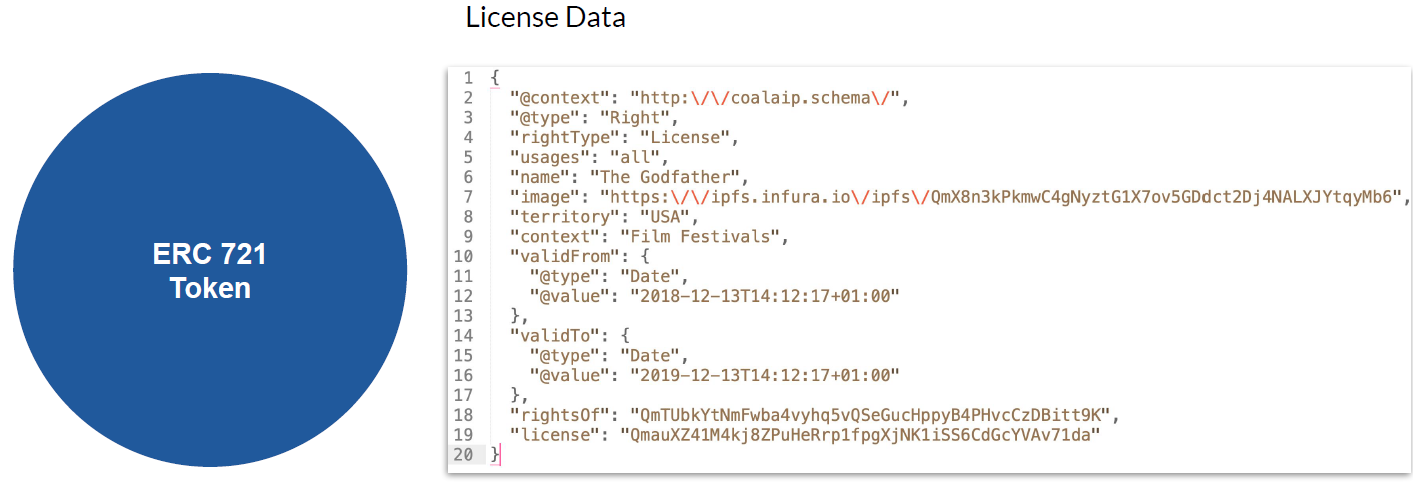

- A concrete standard that has been developed to create the kinds of tokens in this context is called IRC 721 token standard. Thanks to it, you can put down in a standardised machine-readable form the core terms of an IT-licence agreement. It can:

- represent a non-tangible economic good, ancillary copyright, a licence agreement and so on.

- have a unique owner (right holder) or a multitude of owners. Terms of use are programmed into the token. It contains the territory in which you are allowed to exploit that token, time window and the type of use. Such a token is transferrable and you can create a sublicence based on it.

- The source code is already machine readable but not machine-optimised. It is optimised to be written and read by humans like computer scientist, which then will be compiled into a machine code and executed somewhere in the CPU. Certain information, like the licence information, will be represented in another kind of data. The picture below shows, as an example, how a licence agreement looks like when it is stored in a blockchain. All information about the licence are transparent (validity dates, exploitation territories, sublicence info, etc.). The whole chain of providence is visible, showing where a particular licence is coming from.

- Furthermore, when you have this kind of token, you can create many other tokens around it. This process is called the token economy. For example, ERC721 token allows you to create digital securities in order to sell future profits of a film and fund its production. Thus, it is basically a venture financing, fully digitised and fully interlocked with the life cycle of the IP behind it.

Phases in the life cycle of a film in the blockchain era?

- The life cycle of a film in the blockchain era starts with the idea for a film in the form of a copyright-protected synopsis or treatment represented on blockchain by the IP protocol.

- Then comes the financing phase in which the producer sells the digital and token-based securities that embed and certify the future profit to be used for production of the film.

- In the production phase, producers may partly pay the crew in these profit participation tokens.

- Distribution phase will be marked by a very transparent peer-to-peer licence trading.

- In the exploitation phase, filmmakers and right holders will understand easily how their ideas have been exploited along the value chain and will easily claim royalties on that. Royalties may also be paid automatically as they are being created, executing the waterfall.

Two Examples of User-Cases

- License-trading platform called Cinemarket is a user-case that produces the token-based IP Protocol. Basically, every time a film licence is sold, a token is created and is transferred along the value chain.

- White Rabbit is a controversial use-case because it monetises the online piracy. It enables pirates to pay for the films that they illegally stream. Since the blockchain contains the information about the rights and their owners, pirates are actually paying directly to the people from which they steal the film. Netflix has around 30 million subscribers in Europe, while there are 350 million people that are illegally downloading films. Instead of being afraid of Netflix maybe we should be afraid of people who do not know how to pay for the films they are watching and maybe we should start giving them an opportunity to pay for it.

Blockchain 2.0

Blockchain started with a utopian idea, but it did not really work out. Thus, in 2019, blockchain is being re-evaluated. Its reformers need to undertake the following actions:

- To create industry-specific blockchain networks (for example, for a film industry) with concrete user-cases and real value add

- To connect to existing blockchain ecosystems and use the value that has already been created rather than build the new data silos

- To exclude crypto currencies as a means of payment because nobody understands and wants it.

- To provide a scalable and cheap infrastructure that is open for everyone to use.

- To build an ecosystem of applications and users from day one

- To allow every industry to govern and finance the creation of this infrastructure on their own.

How will the film industry participate in this?

- The film industry should create a non-profit association whose membership would represent all stakeholders (the European film funds, producers’ associations, filmmakers, etc.). It would decide how the blockchain infrastructure should work, how it is being developed and financed, and who has power over it.

- Another solution would be to establish tokenized blockchain-based film funds that would insist that the beneficiaries of their funding must use the full blockchain ecosystem to create their films.

Eurimages – the first European fund experimenting with the blockchain technology

Eurimages has set up the working group which is in conversation with a number of film funds and blockchain experts and discusses the introduction of the blockchain technology in the area of European co-productions. They started with harmonisation of the production budget across Europe. The idea was to create a top-sheet suitable for everyone so that producers do not have to change the budget form in every country. The new universal top-sheet is now available on the Eurimages website (see “Summary production budget” on Eurimages website: www.coe.int/en/web/eurimages/documents) and a number of film funds and producers already use it. There are also other topics the working group is discussing right now like how do you register different type of costs, definition of overheads, etc.

Blockchain indeed enables people from the film industry to share at least a minimum of information. Everybody can pick what is necessary, for example, for using a tax incentive, etc. However, it is still all too slow considering how fragmented and complex the European film industry is. Furthermore, Eurimages consists of thirty-nine countries, which makes the whole process additionally challenging and complex. It requires a lot of pragmatism and flexibility. In some countries, you can simply cannot change the regulations.

Q&A with Florian Glatz

- Is the blockchain fully transparent? Can everybody in the industry see the contracts or are there some specific access rights?

- FG: Right now, it is fully transparent. It would take some additional effort from the funds and the entire film industry to introduce privacy.

- When Canada co-produces with Europe, nothing looks the same, it feels like producers come from two different planets. It takes forever for producers to find common ground. If you had a European association who would spend years deciding on a common, standardised architecture, would it solve the problem?

- FG: If we are not able to agree on the data standards, blockchain is useless. We need to agree on the data standards first. Blockchain indeed reinvigorated many efforts to standardise data-sets. Once you standardise them, you immediately benefit from the blockchain. It has a power to get people work on things that have previously been considered totally hopeless.

- For now, the blockchain seems like a dream where everything is automatic. But maybe certain things should be regulated first before they are integrated into a big automatic system such as blockchain?

- FG: Definitely. We need to be pragmatic about all this and start with the areas of the film industry that are less sensitive to the revolution. We first need to identify the area in the industry where introducing automatic systems like blockchain is possible. There are two approaches here. One way is to start with the films that do not exist yet. This means that funds can say that they want to support only the projects that from the start use the digital blockchain to define everything around the film. The second approach is to create a library of films and all the accompanying rights in order to be able to feed them into the block chain and arrange their distribution. But it is up to the funds to choose the approach that suits them best.

- Who is going to enter data into the system and what if entered data is false?

- FG: There are two solution to this. The first (centralised) solution is to create specific institutions that would validate the data entered into the system (especially the copyright-related data). The second (decentralised) solution is to let anybody claim whatever they want and let the time show who was right and who was false. In case of any conflict, the real owner would easily prove his ownership during a dispute process. However, it is again up to the industry to decide on a more suitable approach.

- What will happen if a film fund decides to change the provider of the blockchain service?

- FG: There are two layers here: the ground layer and the application layer. On the ground layer, we standardise and represent the IP agreements. Here we all need a consensus and a common solution that everybody adopts. This should not be done through a single project, company or a private entity, but we need an industry body all of us is part of to decide on this. Once we have this ground layer, we will see a very healthy competition on the second layer, which is the application layer. There will be many companies competing for users and clients, but they will all use the same underling blockchain and the same underling protocol for doing the bookkeeping. For the end-users, such a competitive landscape means that switching costs would be low, because the data portability is already ensured by the ground layer being open and standardised by the film industry itself. So if one service-provider on the top layer starts charging too much for their software, you can switch to another service provider, but your data stays in the same place.

- Would we use electronic signatures?

- FG: To be able to close legally binding contracts through a blockchain, we would need a concept of legally secured digital identities and electronic signatures. This principle is already possible to some extent, but there are currently massive efforts on the EU level under the umbrella of the European blockchain partnership. They are looking for the European framework for developing a digital identity standard that complies with all necessary requirements.

In its blockchain strategy, the German Government said two relevant things. First of all, digital identity is the top priority for Germany and, accordingly, Germany wants to look into how data on the blockchain can be used as a proof at court.

I think all this will be driven by the public sector: governments and regulations, but also by the industries choosing and adopting certain standards. Also, we need to mention W3C – one of the biggest international standardisation bodies for the Internet which developed all the standards that we use today. They are also developing the standard for digital identity called the DID (decentralised identifiers) standard that is already in use. They are also creating another standard, which will be very relevant for the film industry, called “verifiable claims standard”. With this standard and the DID standard, we already have the major standards that will be relevant for the IP protocol - And where does blockchain stand in terms of the energy consumption?

- FG: When it comes to the energy consumption, we are looking at two different generations of blockchain – the bitcoin and what is coming now. Bitcoin users consumed a lot of energy to run the system. Now renewable energy sources will be increasingly used to feed the energy hunger of bitcoin. Already today around 40% of energy consumption of bitcoin comes from the renewable energy like, for example, in Iceland. The Chinese Government will also switch soon towards the sources of renewable energy. The German Government in its blockchain strategy said that when it gives money or projects to private entities to develop something with blockchain, one of the criteria will be that they must use a CO2-neutral blockchain that does not consume energy in the way that bitcoin does.

- There is no database for copyright ownership, which is a big weakness. Where should we begin? This is particularly difficult during the dynamic development and production process of filmmaking. But there are people who are already collecting data for co-productions called collecting agents. They have information like who is the owner of the revenue streams, for which territories, etc. everything that would be highly valuable for a blockchain. Are you in conversation with collecting agents because that could be a good start?

- FG: We should be. Connect us with them, please!

The public film funds’ experiences with new players and forms of content, their impact on funding schemes and their responsibility towards the industry in the 21st century

- Module 1 – Platform Economy

- Module 2.1 – New Formats

- Module 2.2 – Group Exercise: Format Development

- Module 4.1 – Digitisation From Application to Distribution

- Module 4.2 – Blockchain as a part of the workflow

- Module 4.3 – Group exercise: block chain as part of new funding schemes. Supporting new formats and platform distribution

- Module 5 – Sustainability: Surviving the 21st Century

- Module 6 – Free Flow: What Do You Think?