Reports Previous Workshops

Ninth Workshop – 25 to 27 September 2019 in Potsdam, Berlin

Module 1: Platform Economy

Introduction

The emergence of Netflix (more than 140 million subscribers) and other streaming platforms could be considered as a tsunami in the audiovisual environment. They are profoundly changing audience behavior and have a deep impact on film production, financing and distribution. A great deal of money and resources go into the creation of original content for platforms. This huge impact of the digital platforms raises multiple questions for the public film funds:

- How do public funds experience the emergence of platforms?

- How do funds reposition themselves in the changing media society?

- Do they need new formats? How can they support the development of formats without knowing how they will be seen? What are the criteria they need to address when discussing/ evaluating formats?

- Which producer does not dream of selling his/her project to Netflix, Prime Time, YouTube, etc.?

- Should funds deal with platforms directly not via producer?

- Should funds allow their films to go directly to the platforms?

- Do funds go beyond Netflix and Amazon and communicate also with other global and local platforms?

MODULE 1 deals with the current situation of the media platform economy and the developments that we can expect in the coming years. It consists of three lectures followed up by the discussion on how the national funds could or should react and what role the European Commission should play in this area. The idea behind this module is to provide a map showing where the platform economy stands today and where it is going.

LECTURE 1:

An Overview of the Platforms’ Landscape

Patrizia Simone, European Film and TV Analyst/European Audiovisual Observatory

See Patrizia Simone Lecture (PDF)

The VoD Models

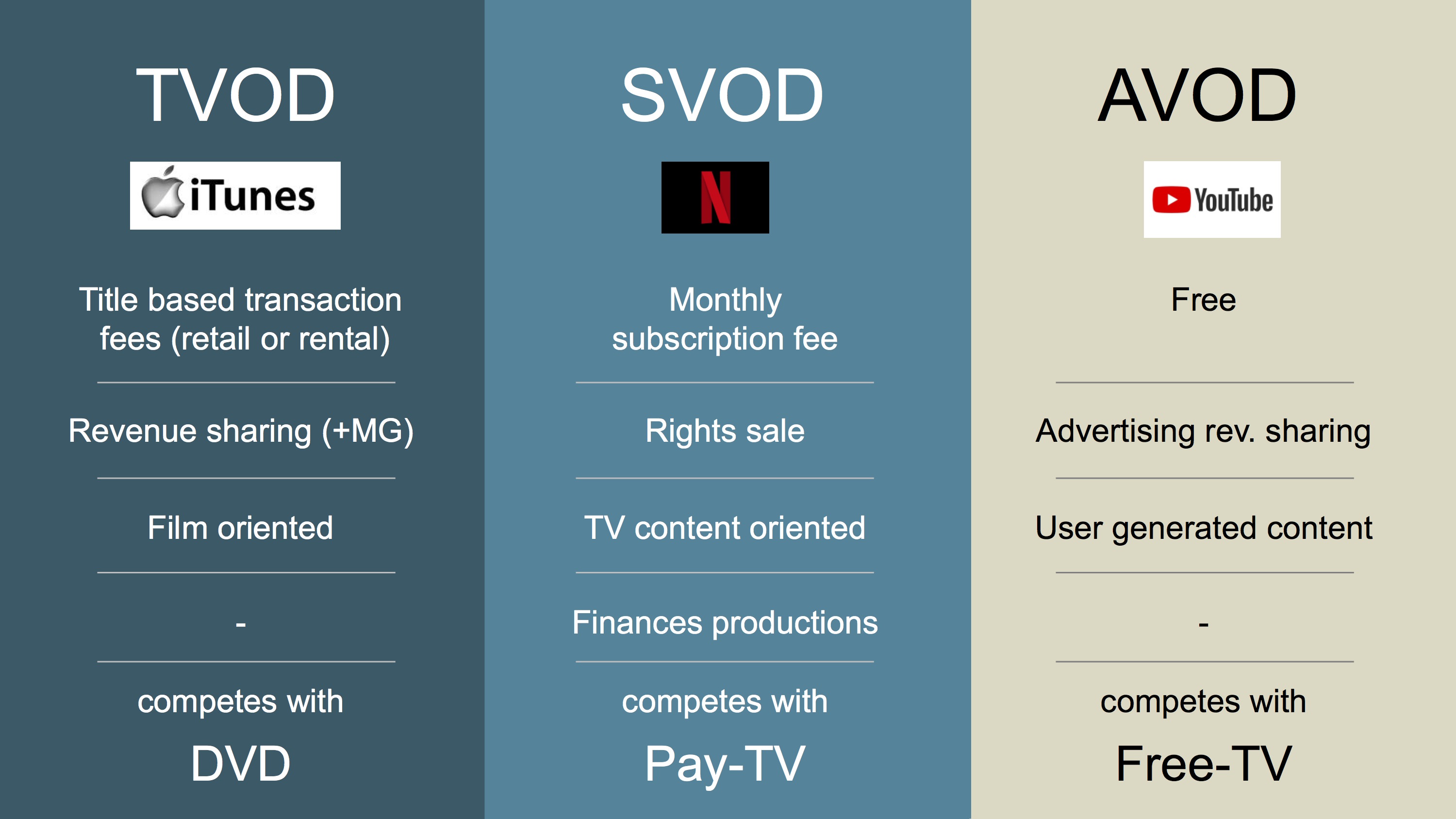

We can identify three different types of VoD models.

- Pay-VoD

- Transactional VoD (TVoD), based on on-time fee payment for film content. In terms of the market competition, it tends to compete with DVD.

- Subscription SVoD that offers the access to a catalogue based on the monthly subscription. These catalogues offer mainly TV content and these platforms finance productions. In terms of market competition, they compete with Pay-TV, which is also based on the subscription model.

- Free-VoD

- AVoD (Advertising Video-on-Demand). It is free for consumers and competes with free-TV. All the costs are supported by advertising.

VoD platforms and Pay-TV in the EU market

Currently, the Pay-VoD is driving the growth in the EU audiovisual market. The figures show that Pay-VoD revenues have been growing quite consistently (+34% over 2106 and 2017) while Pay-TV has much smaller annual growth rate (only 2%) and physical video was under a steady decline (-17%) and more specifically:

- -the SVoD is driving the market with an explosive growth of subscribers over the past years. The revenues are also jumping quickly. However, there is still room for growth.

- TVoD is a less growing part of the Pay-VoD. That may be because it offers mostly films, while SVoD is about the TV content. So, if we have a closer look into the numbers, we see that on SVoD, 80% of the content is TV content, whereas on TVoD, the TV content makes only 2%. But that is only if we count a series as one title. If we break down the series into episodes (giving each episode the status of a title), then 45% of the TVoD content is TV content, while 87% of the SVoD content is the TV content. Therefore, the European film market will not significantly profit from the SVoD, because films do not make a big part of the SVoD catalogues. Pay-TV still represents only a small portion of the overall AV market in the EU. On-demand pay-revenues represent only 5% of the entire EU audiovisual market in 2017. If we compare SVoD and Pay-TV, we can see that while SVoD has been growing much faster over the last five years, Pay-TV is still the dominant player in terms of revenues (35% of the EU AV market in 2018).

- SVoD has become an established part of the AV ecosystem with the rapid growth in terms of subscribers and revenues. The European Audiovisual Observatory estimates that there are around 250 different SVoD services. SVoD also represents the shift in the audience behavior – from the ownership of content to the access to content.

- The increase in revenues on TVoD compensate for the drastic fall of the revenues on DVD even if TVoD has a more moderate growth than SVoD because consumers have more choices to access the content.

- VoD markets have an inherently high market concentration. The two big US players (Amazon and Netflix) dominate the EU market with almost 80 percent of the number of subscribers and revenues (97% in France but 33% in Poland).

- Traditional media players are reacting to this challenge by launching their own services to compete with OTTs (for example, Disney is launching Disney+).

- We are also witness to a lot of mergers and acquisitions so that players can achieve a necessary scale to compete against streaming giants. This also happened on the European scale with the EU broadcaster that joined forces in order to compete.

- There is a shift of power towards new entrants (OTT platforms) and direct over-the-top distribution model. The new market entrants have a possibility to collect data and earn revenues immediately, which is something that has always been difficult when distribution was traditionally mediated by distributors.

It is very difficult for the national players to compete with global tech giants in terms of resources and technical know-how, especially, with an increase of investment into premium and original content.

What is the catalogues of VoD services offered in the EU?

In 2019, the Observatory conducted the research during which it tracked 45 SVOD services and 77 TVoD services. And we identified in total 27000 EU films available on VoD compared to 7000 EU titles theatrically released as first window. Among these 27000 films:

- 24000 titles are available on TVoD proving that TVoD mostly focuses on films,

- and 3000 on SVoD.

- However, the vast majority of films – available on TVoD and SVoD - is available in fewer than 4 countries, while almost 40% are only available in one market. It means that European films still travel with difficulties even on VoD.

There are significant differences among the countries. The share of European films tends to be higher in large markets.

- Most of films available on VoD services (one third) are recent films produced in the past five years.

- 57% of the films available on TVoD had theatrical life, meaning that many films go directly to VoD that in the past went directly to video or to TV.

The new AVMS Directive / quota of 30% EU content on VoD platforms

The new AVMS Directive requires that the share of European content in VoD catalogues must be at least 30% and that VoD must ensure the prominence of the European works contained in these catalogues.

As of today:

- the quota requirement is almost met on TVoD

- on SVoD the share of European films is 25%.

- If we look at the TV content only, the quotas are largely met on TVoD if we count series (not episodes) and the quota is almost met on SVoD. While, if we count each episode as one European work, the share of the European works decreases below the quotas.

Even though the quota requirements are already mostly met, there are still several challenges:

- In the first place there are differences between players and countries. On the one hand, the share of European works is higher in larger markets.

- On the other hand, quotas are not met by some of the largest market players and, to some extent, by some national VoD services managed by broadcasters. It is mostly independent national services which offer a high share of European works.

- Furthermore, the AVMS Directive does not foresee any specific sub-quotas for films that would ensure more diversity.

Availability Vs. Visibility

The most urgent challenge for European films when it comes to VoD distribution is visibility – the capacity to be promoted and reach out to the audiences.

The Observatory conducted a research by looking into a limited data sample of 42 mainstream VoD services in 5 EU member-states (Belgium, Germany, France, the Netherlands and the UK). We did a snapshot of what is promoted on the webpages of VoD services and concluded several things:

- The bulk of promotion (95%) is dedicated to films (mainly the most recent films produced in the last 2 years).

- Promotional spots for European films are proportional to their share in catalogue (around 27%). However, the national players dedicate much more space to the promotion of European works than the international players do. Only a very limited number of films benefit from intensive promotion. 30% to 45% of promotional spots for European films on TVoD go to only 10 films – an extremely limited share of a catalogue.

- The question is who is buying the European content. It is mostly the top international SvoD services (Amazon Prime, Netflix and HBO), but also some national players such as Viaplay (Denmark) and TIMvision (Italy). The more territories they cover the larger their catalogue is, and the more European works are included in them.

There is a common myth that global platforms are interested only in blockbusters. But we analysed the shares of theatrically released films in the catalogues of four major players (the two main US players – Netflix and Amazon, and two European large players – Viaplay and TIMvision):

- Surprisingly, Amazon and Netflix have a higher share of low-performing theatrical films in their catalogues than the successful European VoD platforms.

- At the same time, the share of European blockbusters is pretty much the same across the four catalogues. Netflix has been investing in European films, but with a downward trend in the past three years (it bought 90 films in 2018, 150 films in 2017 and 234 films in 2016). This is probably because Netflix started producing more original content. However, its original production mostly consists of series (in 2018, there were 25 series and 10 films). Netflix has been less and less interested in buying recent European films only for individual territories. It increasingly requires multi-territory rights Right-holders might have difficulty in reaching out to Netflix without a middleman such as aggregators.

The direct investment of VoD platforms into films

The Observatory has recently done a research in how European films are financed. It was based on the limited sample of final financing plans of 445 live-action fiction films released in 2016 in 21 European markets. The sample involves the investment volume of 1.4 billion Euros and estimated 42% of coverage rate. The analysis showed the following:

- The VoD financing is still insignificant, at least for films released in 2016. Only 6 out of 445 sample titles received direct financing from VoD service, which is only 0.1% of the investment volume. (Netflix produced 10 films while around 1800 films were produced in the EU)

- The VoD platforms trigger erosion of consumer revenues in other segments such as DVD or Pay-TV, which may result in lower investments from broadcasters and lower pre-sales. This is what has already happened in France. As a result, there is a need for attracting private investment.

- Another concern is that SVoD services are luring talent away from the film industry because they offer higher salaries and film industry cannot compete with the TV SVoD production industry.

General Conclusions

Regarding VoD Services

- TVoD and SVoD are very different businesses.

- Availability is not a challenge, but visibility is. The question is how to reach audiences amidst an abundance of content, particularly on TVoD.

- The ownership of customer relations results in power over suppliers.

Regarding Public Film Funds

- The public support will become more and more important in maintaining cultural diversity in film production. Already in our sample, 39% of films benefited from either direct public funding or incentives. This percentage is even higher (49%) if we exclude France.

- Public money for the audiovisual sector is continuing to drastically decrease. Distribution should be valued as highly as production by the film funds. Funds should consider funding different formats and changing the definition of film. Film can mean anything that tells a story through the art of the moving image.

- The focus of public support is likely to shift from film to other formats and / as well as from production to distribution.

- The prominence of economic goals will only grow.

- The investment in theatrical film production will decrease in contrast to the investment into AV production.

- There will be fewer films

- The gap between commercial films and “difficult” films will be increasing, and public funding for “difficult films” will be even more important.

- The funds lack data

LECTURE 2:

How the platform landscape is evolving on a global level?

by Fabio Lima, CEO/Sofa Digital and Filmmelier (Brazil)

See Fabio Lima's Lecture (PDF)

Sofa Digital deals with all of the phases of distribution: acquisition, delivery, marketing, reporting, financing. We aggregate the content and deliver to other platforms. We have recently started working on blockchain.

General challenges

- The past decade was marked by the Netflix experience, but Netflix is not the only player and the only threat to the traditional film industry

- People are massively using video on OTT and smart phones all over the world. However, it has been very difficult to explain to regulators, politicians and people from the film industry how and why the system is changing from linear and physical distribution to the digital distribution.

- The business has not changed in terms of content because we are still delivering the same content. We just do it by using a different technology.

Two ways of monetising content

There are two ways of monetising content:

- a revenue-share structure (based on non-exclusive content) and

- A licensing structure (based on exclusive content).

This section explains how these two modes of monetising content looked before and after the digital entered the game

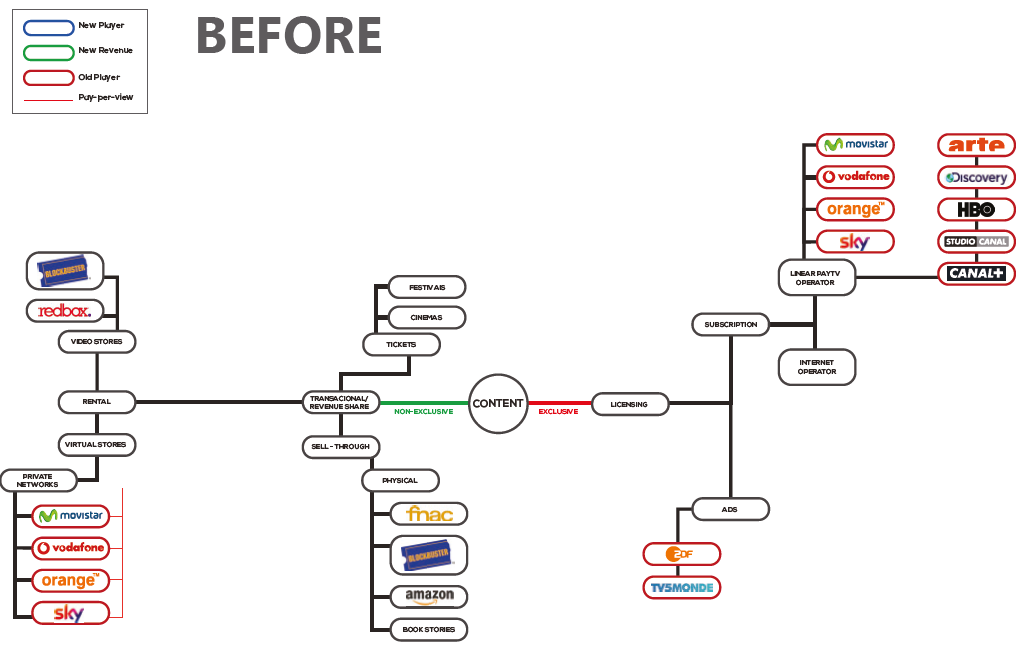

Before

There was one cluster of models of monetising films based on:

- the theatrical window as the first exploitation followed by home entertainment, DVD rentals, etc. Distribution rights were for a particular distributor on specific territories. The licensing model based on exclusive access by media companies so there was only one way in which consumers could access the content – through Pay-TV subscription needing a Pay-TV operator (for example, without the operator you could not access HBO). There was also Free-TV based on advertising and license-fee.

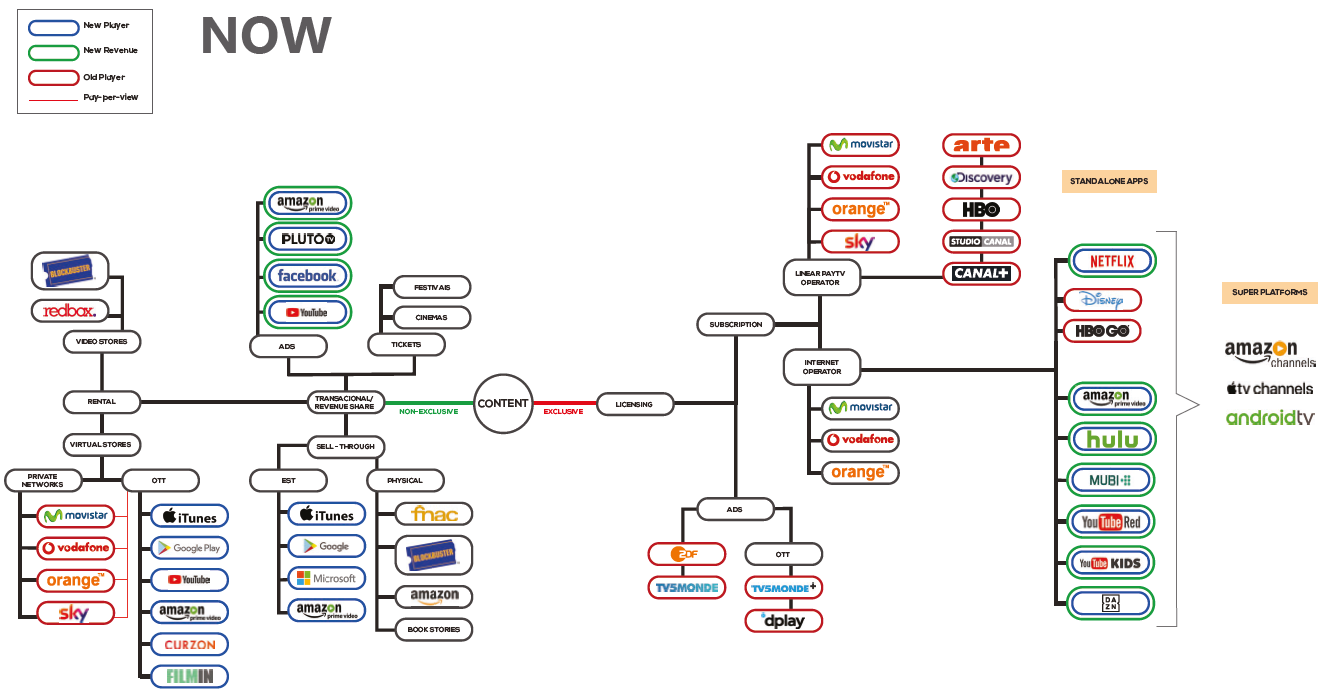

Now

Nowadays, the presence of the digital has not changed the economics of monetising and financing the content. There is still the revenue-share side and the licensing-side. However, there are some new players, new opportunities and more competition because the number of distribution channels is expanding. The age of distribution scarcity and the traditional operation models of theatrical distributors and Pay-TV channels is gone:

- The new digital environment provides an abundance of offers and a better access. The revenues on VoD will become higher than the revenues on DVD because there are no more costs of physical production.

- On the licensing side, there is this a new situation where Netflix and other similar platforms are just one of the providers delivering the Pay-TV type of content. The only difference is that the access to their servers requires the presence of internet operators.

- Furthermore, there is a revenue-share coming from advertising monetised by success. This type of revenue did not exist before because free-TV was just broadcasting. Now, they are paying for the real audience. Such revenues are generated on platforms like Youtube and Facebook.

- Netflix’s new business model is not disruptive. It only delivers content to individual users rather than to everybody at the same time and points to the fact that distributors need to gain a better of knowledge of distribution beyond the traditional TV distribution model.

The digital players and their offers

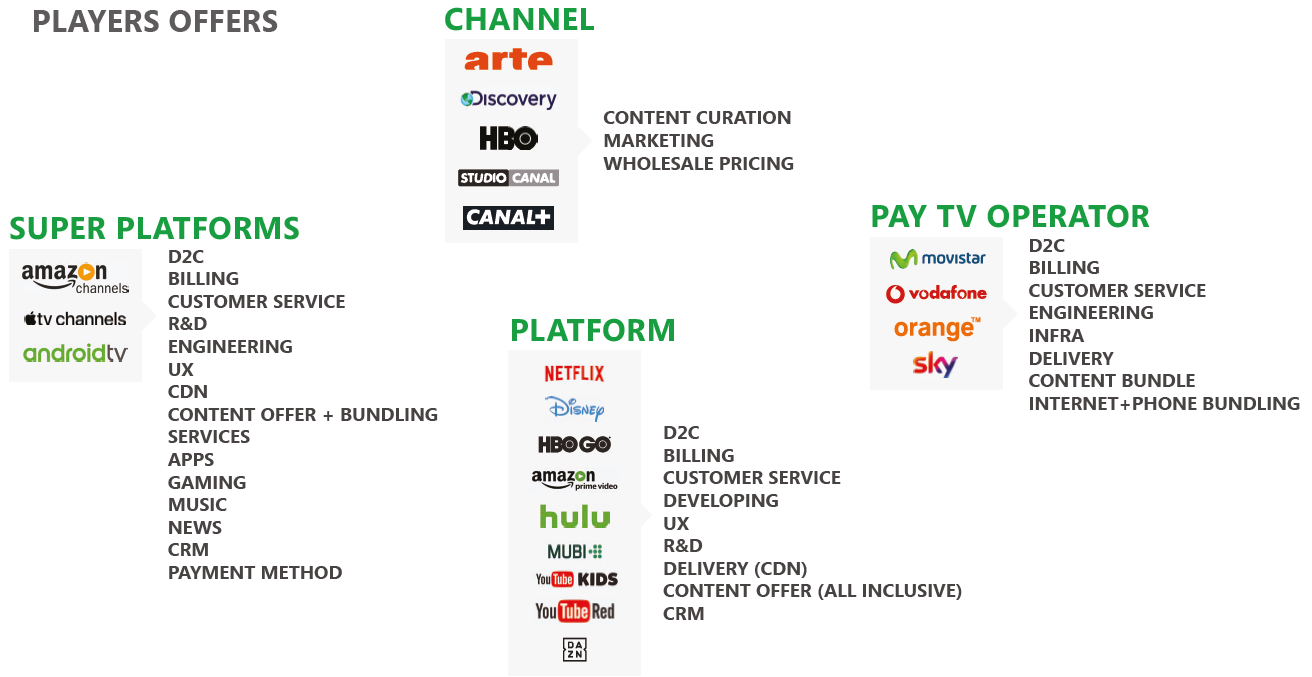

The digital players can be classified into 4 groups:

- Channels that used to be and remain content creators. They co-produce, licence or co-finance content. They offer content curation, wholesale pricing and marketing. Examples of such channels includes HBO, Arte, Discovery, Canal+, etc.

- Pay-TV operators offer direct-to-consumer relation, billing, customer service, engineering, infra, delivery, content bundle, Internet+phone bundling. They have infrastructure to deliver services to content-consumers, to aggregate users and services. The examples of Pay-TV operators include Vodafone, Orange, Sky and Moviestar.

- Platforms used to be only content curators. The major platforms include, among the others, Netflix, Disney, HBO GO, Amazon Prime, HULU, MUBI, YouTube Kids and YouTube Red. They provided a new experience by allowing people to watch whatever they want at any time. They offer direct-to-consumer relation, billing, customer service, developing, delivery (CDN), CRM, UX, R&D, etc. The content offer is based on all-inclusive content. They started by licensing content from all channels at first, but now they are increasingly producing their own content after many channels decided to stop giving them their content. Platforms have the right data, they keep moving and developing, but they are limited in terms of technology.

- Super platforms have two things that no one else does - iOS and Android systems. Examples of super platforms include Amazon channels, Apple TV channels, Android TV. It costs a lot of money to be such a platform and compete with all the other players. Their advantages:

- A half of their employees deal with technology.

- They offer direct-to-consumer relationship, billing, customer service, the R&D that no one else has, engineering, user interface, CDN, content offer + bundling, apps, gaming, music, news, CRM, micro-payment method.

- They are also developing the channel-model. Apple has recently announced the new Apple channel that will be based on the good experience of Amazon channels. Google also announced Google TV. They use their eco-system (apple, iTunes, etc.) now not only to provide film content through their servers to consumers, but also to expand in the way that media companies become able to create their own channels. Soon any media company will be able to create a channel with 200 films. That brings all media companies back to the game again. They can say now: “we neither want to buy nor be like Netflix. We will create a new scale”. Hence, it might be concluded that the coming decade will be marked by the super platforms.

How all this will be reflected in the area of arthouse cinema?

- The Pay-TV players will offer special competitive services and channels dedicated only to independent or local films. It will not bring millions of subscribers, but the channels will have their own way of operation because they are not going to drop any technology-related costs. They will receive a share from the subscription that the super platforms Apple, Amazon and Google will get

- To compete with those super platforms, Netflix will have to focus more on the content than the technology. It will have to become a strong global premium channel.

- Rather than creating their own platform (as Apple and Amazon) Android and Google decided to follow the same strategy they applied to the smartphones and tablets – they simply license their operational system. They created a special Android TV operational tier that can be used by the Pay-TV operators and local platforms that do not have the competency, knowledge or capital to develop their own technology. Now the cable operators will use Android to offer the same services that the main super platforms offer. They pack their own catalogues. You subscribe with a click and receive the same experience as on Apple and Amazon. And that will bring a lot of competition and enable channels to optimise their distribution and have their content distributed across all (international) platforms. For example, if you decide to create the channel with Norwegian films and you want to localise and distribute that channel globally, you will be able do it without aggregators. It will be cheaper. It will change the way we finance content and the public film funds can join this transformation.

The experience of the Norwegian Film Institute (NFI) with big platforms

The obligations of direct investment in European works for VoD platforms implies that some large global players such as Netflix, HBO or Amazon Prime would co-produce or pre-buy a European work that has already been supported by a public film fund. While this can bring an alternative source of financing to European producers, during the MEDICI workshops in 2018 and 2019, representatives of European public film funds raised the following three controversies that so far have been triggered by the involvement of the VoD platforms:

- 1. Would it be acceptable that a film that has been supported by public funds from different countries incl. Eurimages, but attracted no interest by distributors, be sold to a digital platform that takes all the rights, including the theatrical ones, for 15 years?

- 2. Netflix simply does not respect the cultural and protectionist rules of the European public film funds. In reality, Netflix as a US-based company addresses European production companies, does not pay any taxes or levy to the national film funds unlike movie-theaters, distributors, TV channels, Internet providers, etc.

- 3. Finally, acquisitions of European rights by Netflix and other platforms undermine the basic concept of “independent producer” which is at the core of public film financing in Europe. Namely, public film funds and broadcasters in Europe have the mandate to use their subsidy structures to support production of independent works produced by independent producers. However, when producers sell to or co-produce films with global digital platforms that are outside the European system of co-production treaties, totally private, on the stock market and owned by investors, they must give away all the rights and stop being independent producers, which disentitles them from the public support they received from the film funds.

NFI case study

Presented by Lars Løge, Director of Development and Production Department, Norwegian Film Institute

NFI entered into a conflict with the Norwegian production company that co-produced a drama series with HBO. Namely, the producer developed the project himself as an independent producer, which qualified him to apply to the NFI for the production support. The NFI granted the production support on the basis of the great audience potential and a significant cultural value of the drama series. The fund was aware at the time that HBO would also come along as a co-producer. However, when the drama series was well into production, the NFI demanded to see the producer’s contract with HBO and found out that the producer sold all IP rights and ownership to HBO. The contract stipulated that in case of any breach, HBO will be considered as the sole owner of the work.

On the one hand, it was a fantastic contract for the production company in a sense that HBO financed almost the entire series. However, the NFI believes that the producer breached the NFI’s funding rules and regulations by signing this contract because it tricked the NFI into subsidising the global digital platform instead of an independent producer whose works cannot be financed through the market alone. Consequently, the NFI withdrew from the project and asked its money back. For the fund it was unacceptable that the ownership is completely out of hands of the producer while HBO can decide on absolutely everything regarding the project. The producer complained against this NFI’s request and the case ended up at court. The litigation is still in progress at this moment.

The above case raised many issues that the European public film funds may face once VoD platforms start investing more frequently in European works. It signals that some basic terms and concept need to be re-considered:

- What are the responsibilities of the funds and what are responsibilities of the market vis-à-vis production of European works?

- Where do the responsibilities of the public film fund stop?

- Also, clearer definitions of the concepts of “independent European producer”, “primary ownership” and “secondary ownership” are necessary. When does a European producer stop being independent? Does having no or negligible part of the revenue share and copyrights make a producer and independent producer?

The conclusion that the NFI has made is as follows:

- It is positive that producers get more financing choices thanks to VoD platforms.

- Yet, if they opt to get a higher revenue in exchange for 100% of the ownership rights over a work, then the NFI cannot support them, regardless of the project’s cultural value and audience potential.

- The aim of the NFI will be to help producers go to market with a strong IP, rather than as a weak player who will be easily swallowed by the big players.

As the first action dedicated to resolving this issue, the NFI started hosting North American VoD platforms every now and then with the idea that they come to Oslo to hear the pitches by the Norwegian producers who already received some NFI support and intend to internationalize the further financing. In this way, the NFI facilitates matches between the market and independent Norwegian producers. However, if producers choose to sell all the rights to a platform, the NFI will step out and claim its money back. Otherwise, if the platform and producer decide only to co-produce under the conditions that resemble the conditions under the European co-production treaties, then the NFI stay in the project.

LECTURE 3:

Constraints, opportunities, actions to be taken by public funds regarding platforms as a financing partner

by William Page, CEO/FilmDoo-Eurovod (Brazil)

See William Page Lecture (PDF)

William Page is the co-founder of FilmDoo Ltd, a London-based VoD platform that focuses on international films with language and culture of different countries. It is supported by the European Union. He also co-founded the company called Fasso U.G, in Berlin that is based on technology business. He is also the director of Eurovod, an association of European VoD platforms and technology businesses consisting of approximately 400 members from across Europe and internationally.

General trends

- It is self-evident that the times are changing. What we see is the emergence of a number of new platforms, and new ways for the content to be seen. The revenues from the Internet giants increased while the broadcasters and other traditional platforms are declining. That led to the situation that Internet players started financing and producing their own content.

- Netflix is not the only digital player. There are more competitors and new market entrants, which has triggered an increase of non-linear consumption. Children do not watch TV, but YouTube. It affects the way content is seen and the type of content the people want to see. This all resulted in the proliferation of the VOD-platforms worldwide. Several of them are getting very strong (like Disney+ and the new Apple platform) on a global level, which will have a significant impact on the licensing of the content and it marks the end of a Netflix’s monopoly.

- Who are the most relevant audiovisual market players and what are their revenues:

- There are 65 EU public service media. They are considered to be the traditional players and their share of the pie is by now relatively small.

- Then there are European commercial broadcasters (such as Sky, Liberty Global, Vivendi) whose revenues are 1.8 times bigger.

- The European telecom operators (such as Deutsche Telecom, Vodafone, Orange) show revenues that are 8.9 times higher than those of public services.

- The revenues of non-European media conglomerates are 11.2 times higher.

- And finally, the Internet giants such as Amazon, Apple, Alibaba, Facebook, Tencent, or Netflix show revenues that are 18.4 times higher than those of the EBU (European public Broadcast Union). These Internet giants are increasingly commissioning the content and expanding internationally (including the European market).

- Netflix and Amazon are momentarily investing the most in content. However, Apple TV is about to be launched and is already commissioning a number of their own shows. There is also Disney+ that is going to drastically increase the content budget over the next four years. All these platforms are becoming more aggressive with clients.

- VoD platforms are behaving more and more like traditional platforms. A number of platforms pursue exclusive and all-rights deals. Funds should think about pointing local producers towards them because they have money and fund original content, but producers should understand the implications of exclusive deals.

- VoD still makes up a relatively small share of the overall revenue, but growing rapidly worldwide – except for the USA where the market share for streaming has already reached market saturation (Statista estimates that 44% of American households already subscribe to Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu or other SVoD services). but it is ramping up in other markets worldwide. Consumers are spending more on subscription video services than ever before.

- SVoD dominates both in terms of clients and revenues when compared with TVoD and AVoD.

Challenges for film-financing and distribution practices

- VoD services play an increasing role in changing release strategies and in challenging the traditional separation into windows of exploitation. Yet some countries like France rigidly stick to the traditional windows.

- Connected audiences find it ever harder to understand that the film of their choice can be available in Europe or elsewhere in the world, but not in their country. That is where platforms can potentially offer a solution.

- There are many upcoming SVoD platforms (i.e. Disney+, Quibi, Apple TV+, HBO Max, NBCU, BET+) that are ready to invest billions into original content, film and TV.

- Lines are also being blurred between different players. There is more and more collaboration between leading SVoD platforms and ITC/Pay-TV operators (i.e. Amazon and Vodafone, iflix and digimaxis, Sky and Netflix, etc.).

- ITC (Internet and Telecommunications Companies) are also adding/building their own OTT/SVoDs.

- Many SVoD fund “originals” (i.e. Sky original production, a Viaplay original, Atrium TV).

- “Skinny bundle households” make 54.6% share of total OTT viewing time.

Continued industry uncertainty

- It is important to recognise that a number of platforms will not survive because their operation will become too expensive.

- The decline in Blu-ray and DVD sales is accelerating, while digital video spending worldwide is growing (in particular SVoD).

- Change in user behavior – unwillingness to pay for content and growth of illegal apps and ways to grow content.

How to Exploit VoD for Produced Content?

In which chronology?

- VoD should not affect the classic principle of a licensing and release chronology that starts with the highest price for an individual (theatres) and ends with the lowest price for the largest groups (free TV).

- Most European markets place the VOD release and EST parallel to the DVD release (rather than before). This is being increasingly challenged.

- SVoD services seem to be better placed after pay-TV release, until they pay more

- AVoD services should be avoided until significant licensing fees have been gained, as these services potentially dry up the value of a title

- Catch-up TV services do not seem to be a chronology issue, yet the number of views or transfers allowed could potentially dry up the value of a title

Maximising revenue and exposure for independent distributors

- Most VoD platforms are concerned with offering a wider selection of titles than their competitors rather than with maximising revenues of each title.

- It is rarely possible to control the price policy of a platform, but it is always possible:

- not to work with those that dump the market (generally to sell other services, such as Internet access)

- to ask for a guaranteed royalty, independent of the sale price

- The need of for promotional /editorial support is stronger than in any other form of exploitation except for theatrical release (for example, in France, during year 2007, the first 50 films represented 60% of the admissions in theatres, 19% of the DVD sales and 33% of the VoD rentals)

- The long tail theory can be made a reality with strong editorial & recommendational tools.

- Aggregation of independent distributors/producers can obtain better rates and exposure (for example, Universciné and Eurovod)

- There is also the new European AVMS Directive in place that foresees 30% quotas for European content on all platforms. This will give producers more visibility, more prominence and as platforms will need more European content. According to the directive, VoD services will also have to invest in the local European productions.

What does this mean for funders?

- There are more potential digital partners than just Netflix!

- More options than ever before for financing – new forms of advance funding, exclusives etc.

- Funds need to have a ‘global mind-set’ to distribution as there are now more content distribution and players available. For example, Europeans think that people in China only watch Chinese films, but this is not true. There are regulatory issues and censorship, but non-Chinese films do quite well in Chinese cinemas. For example a Thai film was bought by a Chinese distributor for 400,000 USD and earned 41 million USD.

- Blended options for financing and new business models are likely to emerge

- We will see a growing need for co-production worldwide and in the emerging markets

- Funds can use ‘exclusive’, ’originals’ and ‘all-rights’ to maximise value

- Funds need to consider VoD platforms and long-tail distribution in their financing models.

How can funds help producers deal with platforms?

- Opening doors to broadcasters, platforms and ITC.

- Need for education for producers. They do not necessarily understand technology. The funds’ role is to help them there. Funds can join together and create the material on new financing options that they circulate to all producers they work with. They should open the doors to other markets (China, East Asia, etc.).

- Creation of new financing models.

- Increasing focus on distribution, marketing and promotion. Shifting priority from production because there is already way too many films per capita in all European countries.

- New forms of funding are increasingly crucial – crowdfunding, product placement, private financing, etc.

- AVMS directive could offer some assistance!

Group discussion about the funds’ experiences with VoD platforms

What happens with the independent producers’ revenues?

- It seems that sustainability of the independent production companies will not be based any more on revenues, but on the production that caters to the demands of VoD platforms. How can the system ensure that producers are able to receive revenues during the exploitation of the content in addition to earning money while producing it?

- Producers may get one hit on the Netflix-like platforms, (like Rain in Denmark that has become popular globally), but they do not see a lot of money out of it even though it brings them more work through commissioning new seasons and series.

What happens with the IP rights?

- Platforms are more and more open to share the rights with producers. However, producers need to negotiate for months with Netflix to keep the basic rights in their company.

- Producers lack an adequate education and experience in dealing with the sale of IP rights to the digital platforms

- In the case of publicly funded films, producers do not care about them after they produce them. They sell the films for peanuts to Netflix because they are not obliged to pay anything back to the funds. They accept poor deals because they did not invest any private or recoupable money into their films.

- TVoD still has the same concept as theatres. You have a film and you want to buy the experience of watching it, maybe in a different home environment, but you are buying into an IP. But SVoD gives a different experience because you can have access to quite a bit of the content there for little money. The IP you are accessing changes the consumers habits and the attitude towards viewing the content, especially when it comes to children. It creates different way of consumption. But in this new environment, there is a question of how we keep the interest in the product not only in the viewing experience.

- In Asia, there is a proliferation of AVoD platforms. People do not want to pay for the content (especially young people).

How to ensure more visibility for the European works?

- There is no question of the availability of European content, but of its visibility. The funds see Netflix and other platforms as an enemy. Instead, they should collaborate more with them on promotion of the content.

- Proliferation of platforms is an opportunity for producers and funds to make their films seen by more people than ever before. On the flip-side, the public does not understand why they need to pay for a film that is free elsewhere by illegal downloading.

- The 30% quota ensures quantity, but it does not mean that the films will be more visible. This quota should be set as the final goal, rather than as an obligation.

- Subtitles are becoming cheaper and cheaper. Animation films will soon start to be dubbed by the artificial intelligence. This all helps in getting material available in different languages much faster.

- Platforms want blockbusters and promote only very few titles, but they should go for more diversity. Festivals show some great Netflix original films that would have never been made in the US without this streaming platform. Can Netflix start co-financing in the same way small documentaries and arthouse films from small European countries?

- High-quality content is high-quality content regardless of where it comes from. There are examples of British pensioners becoming obsessed with watching a Thai series. Platforms can be great partners in production of such high-quality and universal content.

A synergy of the new and the old platforms?

- Netflix and MUBI are trying day-and-date release more often. This can work for specific art-house films, but some middle-brow films can suffer from the disruption to the theatrical release model.

- Netflix offers only limited theatrical release (in few cinemas, only in one territory, etc.). They use theatrical release only to obtain some additional promotion while the rest happens on the Internet. Netflix cares only about the online audience. Theatres cannot remain sustainable with such a system because once a film in on SVoD, all the revenues remain there. With TVoD it may work better.

- In the UK, there are examples where distributor, exhibitor and SVoD platform join together to do only day-and-date. For a number of films, it really works; cinemas are packed and platforms are selling well. Maybe other local cinemas across Europe should try to develop similar synergies with VoD platforms where everybody may benefit from the same marketing.

How to regulate the new platforms so that they contribute to the implementation of cultural policies, especially in small countries?

- SVoD’s regulatory future is unclear. The funds have no idea about how to finance productions meant for these platforms. And there is a need for that because there is an overproduction of movies and all of them cannot have theatrical releases.

- Netflix has the same model as Pay-TV: both will be moving to channels. It will change the framework of regulatory discussions. Local and niche channels will enter the market, which is relevant both for film funds and the policy-makers in small market.

- Film funds should support local platforms to join forces and acknowledge that Netflix is not the only option. There must be a regulatory framework that would support cooperation between small, local platforms.

- On the one hand, platforms need to be forced to pay levies similar to the traditional players. On the other hand, small European platforms like the ones that are part of Eurovod simply cannot afford to pay them.

- Netflix keeps all the data for themselves or sell it. Can a regulatory framework oblige them to share some of the data with the public film funds?

The public film funds’ experiences with new players and forms of content, their impact on funding schemes and their responsibility towards the industry in the 21st century

- Module 1 – Platform Economy

- Module 2.1 – New Formats

- Module 2.2 – Group Exercise: Format Development

- Module 4.1 – Digitisation From Application to Distribution

- Module 4.2 – Blockchain as a part of the workflow

- Module 4.3 – Group exercise: block chain as part of new funding schemes. Supporting new formats and platform distribution

- Module 5 – Sustainability: Surviving the 21st Century

- Module 6 – Free Flow: What Do You Think?