Reports Previous Workshops

Third Workshop Report — 17 to 19 September, 2013 — Château de Limelette (Belgium)

The Decision-Making Processes

Please also the “Summary of decision processes and methods of some funds” (PDF)

Module 5 – Goals and selection processes/methods

The decision process is key in the management of public funds. There are different types of selection processes and decision-making schemes among the European public film funds. These depend on the size of the country, the goals of a particular fund, and the way in which the fund is financed. Whereas collaboration exists among the regional European funds, harmonization among the national European funds seems highly improbable. However, funds can learn from each other’s practices and copy some of each other's ideas.

Presentation of the funds' selection processes

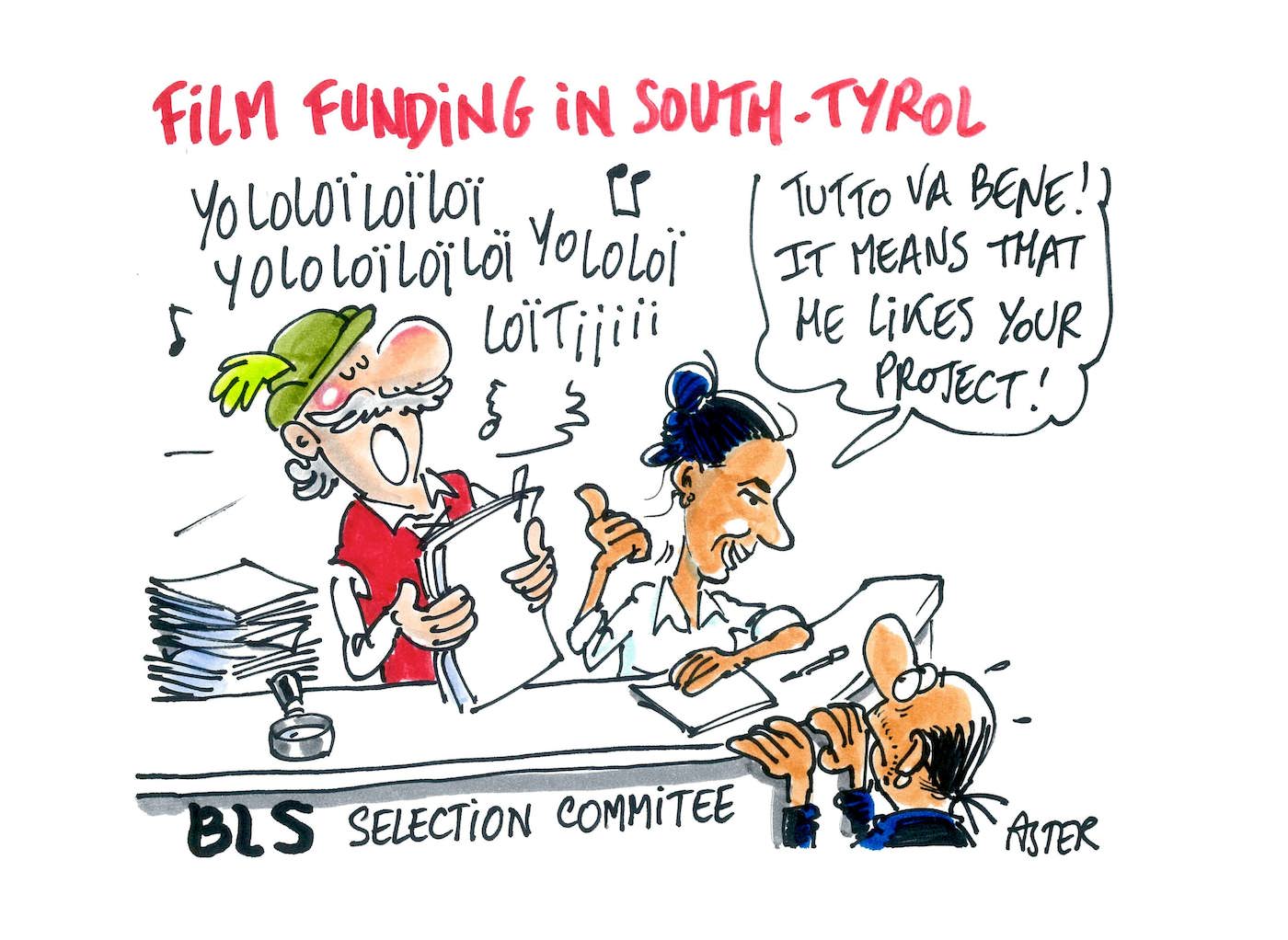

1. BLS Film Location, presented by Christiana Wertz, Head of Film Fund & Commission

General characteristics

BLS Film Location is a fund in the Northern region of Italy. The population of this region is 70% German- speaking and 30% Italian-speaking, which has a certain impact on the selection process. The fund was launched in 2011. Its budget is 5 million euros a year, and it is 100% publicly funded. The region's Department of Trade and Industry provides the fund's budget. Considering the region's size, it is a big fund, and that is why the population is highly interested in what we are doing. Therefore, too, the pressure to justify what we are doing is pretty high. BLS offers two funding schemes. One is for production funding, and the other for development funding. BLS is a selective fund: there are three calls per year for both schemes. During each call approximately 35 applications arrive, and around 25 projects are supported per year.

BLS’s major goals are achieving an economic impact and increasing the visibility of a project. For that reason it often supports small projects and sometimes even projects with only VoD release, because small projects tend to be more open to hiring less experienced, young and local crew members.

What does the decision process look like?

Macro perspective

From the macro perspective, there are three steps to decision-making. First comes the application process: we have an online application process. Next the expert committee meets and hands down decisions within five weeks. Formally speaking, the expert committee's role is an advisory one. The local government makes the final decision, and it takes another two weeks before the expert committee’s decision gets approved at the political level. Thus far, the government has approved 100% of the projects selected by the committee, but the disadvantage of this system is that it is time-consuming and, to brief the politicians, it requires a lot of paperwork. The role of the fund itself is to mediate the entire process.

Micro perspective

From the micro-perspective of the selection process, there are three levels to the selection process. At the first level, we carry out evaluations of the projects. We check if the formal criteria are OK and if all required documents are at hand. We submit the project to a cultural test, as imposed by the EU, and we check into the potential local economic and cultural impact. That takes one week. We thus prepare the projects for the detailed evaluation to be done by the experts.

At the second level, the experts perform a qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the projects, based on the questions that reflect our goals and our selection criteria. The entire evaluation is performed online. Qualitative analysis means that the experts are invited to answer the questions and to make some comments, and then they assess different aspects of the projects using a 1-10 grading scale. The questions asked have mostly to do with the financial plan's plausibility. Then they send us their assessment (the experts have four weeks to assess the projects). We assemble the results and prepare for the meeting, where the projects are discussed and then submitted to a simple majority vote.

Why did we decide to have a committee of experts although it plays but an advisory role?

The committee is composed of industry experts from Italy, Germany, Austria and Switzerland - the major markets the fund considers. Mainly producers sit on the committee, in addition to some local representatives from the cultural sector. There are no broadcaster representatives. We seek to bring together pools of knowledge from the various markets under consideration. The industry experts are usually bilingual (German and Italian). Through this selection method, we also wish to enhance the fund's credibility, to make it more transparent, stronger and less vulnerable to attacks by politicians and film industry professionals.

What is the role of the BLS in the selection process?

BLS has the final responsibility for the selection, ahead of the government. In addition, the fund moderates the selection committee’s meetings, and I am the ambassador of the fund's major goals. We double-check the selection, using an Excel tool programmed on the basis of the fund's goals and stakeholder analysis. We define certain types of stakeholders, local producers, local governments, and producers from outside the region with different interests in our fund. For every call, we input key project data—like the number of shooting days, local spending in the region, etc.—to Excel, together with the experts' assessments in quantitative terms, and we obtain the ranking of the projects. Also, different rankings are possible. Rankings with stakeholders are based on the experts’ opinion. This tool is good because it lends transparency to our work. It also serves to justify our selection, and is helpful during the selection session itself, allowing us to explain to an expert defending a project that the project ranks poorly as to local spending, for instance.

The challenges

- A film fund's role as a moderator vs. that of defining a clear agenda

- The experts' advisory role vs. their subjective preferences

- The fact that the Experts work in an honorary capacity (no shareholders)

- Number of Experts and number of projects

- Cultural issue / no fixed quota, language issue

- Formal funding decision by regional government

2. German Federal Film Fund, presented by Peter Dinges, CEO

The Fund's objectives

- The objectives we want to achieve are based on a project’s quality and on how profitable the project is for the German market. The Fund also evaluates its own work: we asess the commercial success and box office gross of every single film. We also consider a film's festival record and cultural success.

- What we try to achieve by the end of every decision-making session is the fulfillment of the portfolio idea. That means that if your committee entails opposite tendencies, i.e. favoring smaller and culturally-targeted projects on the one hand, and big ones on the other, than you have to compromise Thus, we try to provide support for various types of films: small projects, big projects, children's projects, new-talent films, creative documentaries, etc., and then we offer a complete portfolio of German films, as copied from the CNC.

Selection process

The German Federal Film Fund (DFFF) exists since 1968, and it has its own traditional selection process form based on the CNC model, which also exists in several national film funds across Europe. We have a selective scheme and an automatic one.

Selective Scheme

The selective scheme follows tradition, in the sense that it is based on a committee. This committee consists of 12 experts. Professional associations are in charge of designating the appointed experts, whereby we seek to create industrial democracy and a transparent decision process. The selection committee consists of authors, directors, producers, distributors, video-distributors, movie theater-owners, and politicians (one member of Parliament and one member of Government). The committee appoints a Chairman to conduct the meetings. We simply moderate the discussion, and the discussion process itself is not based on any point system, but on a free discussion. Decision-making is based on the expertise and personal taste of the committee experts: these are divided between those who believe in the strength of a story, and those who, belonging to the film industry and thus more interested in economic issues. A natural tension thus crops up between creative and commercial aspects or culture, i.e. culture and economics, within the selection committee. We receive between 140 and170 applications a year. The selection committee holds its two-day sessions five times a year, selecting approximately 40-60 projects a year.

Automatic Scheme

Automatic programs are friendly towards producers and the industry in general. Within this program, producers can calculate exactly how much money they are going to make: they can insert that figure into their budget. This is not the case with the selective scheme under which, even if a film is selected for support, you never know how much money you will be getting. And this all the more so should the fund decide to support too many projects and therefore allocate less than requested to each. Some projects end up getting only 50% percent of the sum on their application.

The challenges

- The choices made by our selection committee are sometimes criticized for being overly opaque and commercial and inefficient funding because it is based on heuristic approach. We have to prove that such an approach, together with our reliance on film experts, represents the best choice for selecting the projects, rather than economic considerations, which tend at times to bias the state of mind in Germany.

- Due to the large number of applications, it is impossible to have one-to-one meetings with individual applicants or to provide them with a longer report for each individual decision.

Questions to Peter Dinges

- What kind of project-related material do the experts get to evaluate the projects?

- The material that the experts evaluate consists of a so-called package (the creative and commercial elements of the project, including director, cast, etc), a financing plan, relevant calculations, the script, proof that a distributor interested in the project exists. Unlike regional funds, we support only movie theaters, and no other platforms. That is what makes the existence of a distributor so important.

- Is there any direct contact between the experts and the applicants?

- There are no one-to-one meetings between the committee experts and applicants before a decision is made.

- How often do you change the experts?

- Experts are replaced every three years.

- What kind of movies do you support?

- Only feature films and documentaries.

- How do the experts vote?

- Regardless of the number of experts present, seven votes are always required to obtain a positive decision.

3. Swedish Film Institute (SFI), presented by Hjalmar Palmgren, Head of Production Support

The main characteristics of the SFI model

In Sweden, we face the problem of being a small country, with a small Swedish-speaking population (only 10 million people). The smallness of our culture makes a challenge of supporting it. Our main objectives are to support the industry overall—that is, in its commercial aspect, its Swedish aspect (language and environment), and its artistic impact.

The Film Agreement (which is an only Swedish specificity) is drawn up between the Government and different partners from the film industry. In line with this Agreement, half of the SFI’s money comes from the government as pure tax money, whereas the other half basically comes mostly from ticket sales, from levies and, a small fraction therof, from the public TV and producers association. This Film Agreement allows us, as a Fund, to communicate with different segments of the film industry, while enabling the latter to have their own influence as well.

Selection methods

The Swedish Film Institute is part of the classical Nordic system of film selection and support. We have commissioners: currently, they come to six, each with his/her own area, budget, and personal responsibility for their selections. In addition, there are also people to take care of the administrative work regarding the projects: they handle the economic aspects and budget, providing the commissioners with information as to the amount of funding that the SFI should and can allocate to a project. They can suggest, for example, an increase in an allocation in order to render a project sustainable.

On the one hand, it is important to have a common strategy for all the commissioners. However, it is also important for each to be able to choose his/her own way of selecting projects. Making choices individually upholds the whole idea of personal responsibility for one's decision.

We have two commissioners for feature fiction films, one commissioner for documentaries (from short to feature-length), one for short fiction films including short documentary films, one for co-productions and TV dramas and one for the “moving Sweden” development scheme. The latter exists in collaboration with the Swedish TV and regional film funds, and is meant for more experimental and innovative projects with lower budgets.

The SFI also has a fairly new automatic scheme. The idea behind it is to support films that contribute to the industry. Supporting the industry through such a scheme makes sense because a stronger industry contributes to the arthouse scene as well. The money that goes into the automatic system comes from box office ticket sales.

The challenges

- The automatic scheme takes money away from the other support schemes—from the commissioners, for instance, who can end up with so little money that they can no longer operate or have to save their support for a very limited number of films. The less we resort to the automatic scheme and the more artistic activities and art-house films can flourish. What we call “middle-films” (those that do not aim at big audiences) are particularly vulnerable to this scheme.

- The challenge regarding the commissioners is that the appointed person can simply turn out to be ill-chosen or lacking in communication skills, which can create frustration among some producers.

Questions to Hjalmar Palmgren

- How long is the tenure of a commissioner?

- Tenure for the Film Commissioners supposedly comes to 2+2 years, but most of the time they stay in this position less than four years.

- Do commissioners develop only those projects that will definitely go into production?

- It does not make much sense for film commissioners to put a lot of money in developing many projects if only a fraction of them gets to be put into the production subsequently.

- What are the budgets of the commissioners?

- We have around 12 million euros for all the commissioners and, at the moment, the automatic scheme stands at 3 million euros.

- Are there deadlines?

- No

- How often does it happen that a commissioner realizes a project is not going really well and decides to stop it?

- A commissioner does that whenever he or she loses control over a project.

- How many applications do you receive?

- We have around 1200 – 1300 ideas presented to us every year. It could be either the script that is sent or at first just meeting with the applicants. Commissioners have a very close relationship with the project, and they sometimes collaborate up to two years before the actual decision is made. In the final stage, we support 10% of all applications. But we give development support to up to 25%. This number includes all kinds of projects.

- How active are commissioners in influencing the artistic elements of the project?

- That is individual. In Sweden, traditionally commissioners do not interfere a great deal in a project. This is not the case in Denmark for example, where commissioners intervene more. I am not sure which model is better. They can say that they don’t trust a chosen director, or that they won't support a project if a certain crew is selected. Sometimes applicants complain that the commissioners interfere too much, but very often they are happy to have an outside person to advise them.

- Can a commissioner ask for outside readers?

- This is not typical of our system, but the commissioners are allowed to do so if they wish. They often do.

- How similar are they to the commissioning editors working on TV?

- The difference is that if you are a commissioning editor on television, you need to re-edit this thinking, because TV will not broadcast it. And, too, they are also often co-producers.

Outcome of group discussions

- Is there “the” ideal method, or can various methods be complementary?

- Are these methods transparent enough for the producers?

- How “co- production–friendly” are these methods?

1. Is there “the” ideal method or can they be complementary?

Selection committees Vs. Commissioners system

The upsides of the Selection committees are:

- It is easier to explain to the politicians that the decisions are being made by a group of experts, which is more credible than having only one person do the deciding.

- Selection committees can be composed of various industry professionals representing their activity. Committees can contain representatives from every walk of film industry life—-ranging from technical to very artistic segments (like in Germany).

- It is well-suited to bigger countries with plenty of applications.

However

- Selective systems can create greater distance between applicants and decision-makers.

- In the case of selection committees, experts judge their colleagues. Decisions are sometimes more about making compromises than about being courageous.

The upsides of the Commissioners system are

- Greater transparency.

- One single person makes the decision during all phases of a project. There is an ongoing relation between the commissioner and the producer, which is not possible in the case of selection committee.

- In the commissioning system you cannot hide behind the group as the sole decision-maker.

- Commissioners are a true support to the production team because they are not involved in the financing end. They are the only ones there focused on the story and nothing else

However

- If there are human relation problems between a producer and any commissioner, producers (i.e. those with commercial projects that as yet have no backing) have no other alternative.

- Such a system cannot function in big countries like France or Germany, due to the huge number of applications.

- The Nordic system needs elements from other systems as well, like automatic schemes, and stronger connections with the market.

Automatic Vs. selective scheme

- Selective schemes exist in culturally-driven funds that emphasize the artistic quality of a project.

- Automatic schemes should reward those who have already proven themselves.

- There is a need for smaller automatic schemes or industry-driven schemes in addition to cash-rebate schemes that facilitate inward investment.

- Automatic and selective schemes must be clearly divided, not combined. Applying quantitative measurements to qualitative things would have absurd results.

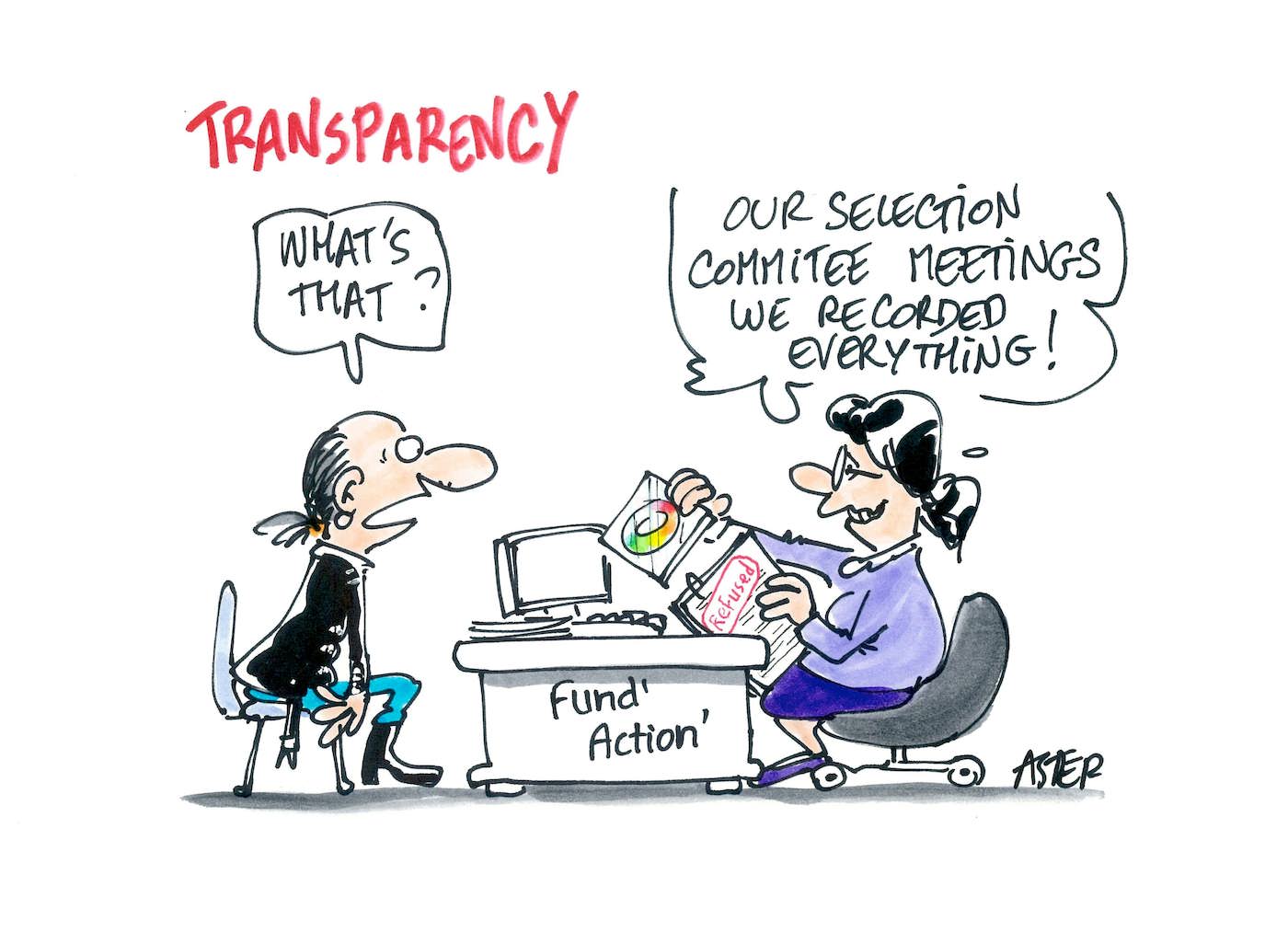

2. Are these selection methods transparent enough for the producers?

- Decisions should be explained to producers at greater length. But how transparent can a fund be?

- Funds should keep talking not only to producers, but also to scriptwriters, directors, etc. and be able to justify their decisions. Constant dialogue creates a bigger picture. This takes time, daily work and personal input.

- The amount of paperwork producers must do should decrease, and the budget forms should be more synchronized.

3. How co-production friendly are these methods?

- Reciprocity problems:

- Even if a selection committee is open to fund coproductions, the coproducing countries do not fool anyone (i.e. Hamburg Film Fund invests 1/3 of our money in co-productions with Denmark or Sweden, or Turkey, traditional co-producing countries).

- Reciprocity is disrupted by the amounts decision-makers have at their disposal (i.e. Croatia invested 800 000 euro in co-productions in 2010, whereas Denmark spent 1,5M€).

- France towards Belgium and Luxembourg: there is real unbalance between money spent on French projects in Belgium (4 times more than in France) and in Luxembourg (no Luxembourgish films at all supported in France).

- Creation of specific coproduction agreements to strengthen funding possibilities between major partners sharing the same language, and to decrease the paperwork, e.g.

- the Swiss-Austrian-German tripartite agreement created one year ago;

- the agreement between the Netherlands Film Fund and the Flemish Film Fund, with decisions taken by representatives of the two funds twice a year, as well as reports by the experts.

- Decisions taken by the CEO of a fund alone (i.e. the CEO of the FFA can exceptionally take the decision alone in case of a total misbalance in the number of supported films between the two sides).

- Not an issue for the regional funds since, in the majority, they do not require projects to be officially coproduced.

Impact of Digital in Film Business and Production

- Introduction — The Perfect Storm/The Workshop Method — PEST analysis

- Module 1 — Should we support less films for an overcrowded market, or focus on ensuring that the films we select find audiences on new platforms?

- Module 2 — How does the dramatic increase in audience data and a demand-driven economy affect our decision-making processes?

- Module 3 — How far do we need to adapt to new business models, and how far can we seek to protect traditional industrial structures?

- Module 4 — Conclusions

Decision Making Processes

- Module 5 — Goals and selection processes/methods

- Module 6 — Selection criteria

- Module 7 — Profiles of experts, consultants, selection committee members

- Module 8 — Relations with higher authorities and producers

Illustrations by Jean-Philippe Legrand – called "Aster"

Schedules Previous Workshops Partners Contact